Make Consciousness Great Again.

Ontopoetics 3: A journey towards idealism.

I have been wrestling with theories of consciousness for a few weeks, and I am beginning to see why the perennial wisdom that “we are all one” is not sentimental rhetoric but clear-eyed recognition. For those who believe “a transformation of consciousness” may be necessary to address the challenges of our times, even if not sufficient, it behoves us to understand what transformation could mean, and what consciousness is. This post seeks to make sense of the latter with the former in mind.1

What follows was a joyous struggle and is likely to be my last post for Perspectiva for a few weeks. I will soon send my phone and laptop on a rocket to Saturn, surrender to fallow time, sing along with The Pogues to the quintessence of post-tragic cheer, and dance with the figurative snow. The Substack superego is guilt-tripping me by saying this post is too long for email, even at Christmas time, so reading it all is a noble and subversive act; scan and look away if you must, or please do get stuck in, but be ready to click again at the end for the full festive feast.

In terms of Perspectiva’s major aims, understanding debates about consciousness is necessary for clarifying the nature of ‘the flip’, the first of three major epoch-defining challenges in the back-of-the-envelope plan to change the world known as ‘The flip, the formation, and the fun’.

Thank you for your support in 2025. If you can like or share, or comment on this post, that is appreciated, and if you feel so moved, you can take advantage of a 25% discount offer to keep Perspectiva’s work going by becoming a paid subscriber, so we can keep our material freely available. Plans for 2026 are already brewing, but for now, it’s time to guide 2025 to its manger, and let the heavens do their thing.

Jonathan Rowson, Perspectiva Co-Founder and CEO.

I wonder if Joe Bloggs and his Aunt Sally know what is meant by the term consciousness and why it is considered by some to be mysterious and confounding. They might be surprised to learn that the most self-evident thing in the world - our subjective experience - has been called into question as an inexplicable anomaly. Consciousness is not physical in nature and cannot be understood or measured in the way physical things can be. Nor is it clear how consciousness could ever arise from physical things, or interact with them. If you work with the assumption that the substances, processes, and events of the world are ultimately physical, it appears to be impossible to adequately explain the most self-evident feature of life, namely, our experience, which is embarrassing, or at least ought to be.

There is still the reality of technological incursions into the lifeworld, the challenge of plutocratic power, the sinking small island states, the men in balaclavas with machine guns…So let’s not fall into spiritual bypassing. But equally, let’s not forsake the possibility of a radical shift in the perception of context for millions of people who are not ready to give up on the world. Many who are not yet mobilised might need to see the world anew to organise with the requisite clarity, determination, and conviviality.

The inquiry that matters is not so much “what is consciousness?” because the answer is unlikely to be a simple what, but more like a complex how, an abiding why, a flowing when, and even a pervading who. It’s probably not a where, however, and that matters too. Consciousness may interact with your brain and body, but it is looking increasingly unlikely that it’s made from them. You might say consciousness comes from elsewhere, but more likely it didn’t come from anywhere at all, and didn’t have to. Perhaps experience is like Tom Bombadil, and just is, and always was. And if, as appears to be the case, consciousness exists in time, but not in space, our challenge as humans is not to locate consciousness, but to make time a better place to be.

Theories of consciousness are ostensibly about the nature of experience, but what’s often at stake is the significance of subjectivity. It’s all very well being a being, but what is exciting is knowing that you are, and querying why you are privy to that knowledge. Our tacit theory of consciousness shapes our sense of what is politically possible, even when, or perhaps especially when, it is held unconsciously, so I am curious to know what happens when we become more conscious of our working theory of consciousness. There is, for instance, a connection between metaphysical materialism and economic materialism. A world with a better balance of extrinsic and intrinsic values is hard to achieve when matter is considered bedrock, and finding bedrock feels like ‘the bottom line’.

The inquiry that matters is not so much “what is consciousness?” because the answer is unlikely to be a simple what, but more like a complex how, an abiding why, a flowing when, and even a pervading who. It’s probably not a where, however, and that matters too.

I also believe that philosophical materialism - broadly the notion that mind is reducible to matter - is actually already dead. Yet, it lives on as the undead, a well-dressed zombie sitting as Chair of the Board with a big smile, awaiting quarterly returns. My aim here is not, of course, to kill a zombie, nor to reach a final verdict on the nature of consciousness, but it felt timely to open the inquiry for those who may not be familiar with it, share my learning in solidarity with those who are also on the way, and indicate why I think this inquiry matters.

A major paradigm shift is underway, but it’s currently discussed mostly in backwaters like this one, and we may all have a role to play in it becoming a wave, and then the ocean, which incidentally is roughly how I see our relationship to consciousness, too. As Rūmī writes (in the Mathnawī):

The wave is the sea itself; do not be mistaken.

**

The idea that we are all part of one cosmic mind, or world soul, sounds trippy to some, but I see it now as a kind of radical sanity. This idea is central to what Aldous Huxley called The Perennial Philosophy, and is implicit or explicit in most major religions. However, it is also an idea with a forsaken intellectual dignity that we need to recover. Debates about theories of consciousness are neither themselves a spiritual practice nor the transformation sought, but engaging with them is helpful intellectual underlabour. Last summer, a post by Ellie Robbins called This Moment Needs Your Deep Weirdness and Your Intellectual Rigour clearly said what many were feeling, and I was glad to see these ideas reaffirmed by Douglas Rukoff, who put it more directly a few days ago: Why I am Getting Weird. I don’t find either of them weird in the modern sense of strange, discomforting or eccentric, but they are weird, and helpfully so, in the older sense of weirdness as destiny, or fate already spun.

Earlier this year, I listened to season one of The Telepathy Tapes. I felt it overplayed its hand, and though I was gripped by the early episodes, characterised by cautious and sceptical inquiry, I began to find the music manipulative, and the emphasis on expansive love too generic and even coercive. Even so, I was impressed that what is essentially a parapsychology podcast about autistic children communicating telepathically made such a compelling case that it briefly dethroned The Joe Rogan Show on Spotify. The podcast did not feel like pseudoscience or ‘woo’ to me, but more like finding a chest of buried treasure in the garden, while not yet having the tools to be sure of its value (or its safety). Kafka famously said that “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us”, and this podcast felt a bit like that. I still don’t know what to make of the evidence of the telepathy tapes or the inferences made from it, but I did see the podcast as a kind of Kuhnian anomaly entering popular culture, asking us to radically reimagine what some minds are capable of and what follows for our view of the world, and what is possible within and beyond it.

**

I am not an advanced meditator, but I have practised TM at least daily for a quarter of a century. In most sessions, my mind is like a washing machine spinning through random images and defragmenting with only moments of stillness, but there are occasionally sessions where I find myself sinking deeply into a form of experience that feels boundless, creative and generative. In such moments, it feels true to say that I am conscious, but not conscious of anything in particular, such that I wonder if maybe I am part of consciousness as such; this very idea puts me at odds with much of the Western tradition that links consciousness to individual minds, perception, and intentionality, but I know it from the inside.

In a famous essay from 1974, “What is it like to be a bat?” Tomas Nagel framed the idea of consciousness as ‘what it is like’ to be something from, as it were, ‘the inside’. He contended that we can’t really know what it’s like to be a bat, even if we understand a great deal about it from ‘the outside’, for instance, its use of echolocation to see, or its penchant for sleeping upside down. Some say that this ‘what it’s like’ experience of interiority is a kind of illusion arising from neurons firing, but as Rowan Williams once put it, our very idea of illusion presupposes consciousness, so if consciousness is an illusion, what isn’t? Some years later, in 2012, in a book called Mind and Cosmos, Nagel surprised the philosophical world by stating the obvious, namely that mind is not reducible to matter, to great consternation and criticism from his peers, including Steven Pinker, who tweeted about “the shoddy reasoning of a once-great thinker.” Yet on page 51, Nagel writes:

If mental phenomena are not physically reducible, then we must expect… a major conceptual revolution in our understanding of the natural order.

And let’s hope so.

But how much does this inquiry matter? As indicated by the Landscapes of Consciousness research that I’ll come to in a moment, our perspectives on consciousness have implications for whether AI might ever be conscious, whether our consciousness could ever survive digitally, whether there is life after death, what it means for life to be meaningful, and the indirect implications go even further. Jeffrey Kripal, for instance, believes we need a new paradigm of consciousness to save the humanities by ‘decolonising reality’ from materialism, and theologians see in consciousness a pathway to primordial subjectivity, I-am-ness from the very beginning, and through that to God. There may also be other psycho-spiritual implications, because anomalous experiences begin to look like they could be a form of intra-mental communication within a cosmic mind, rather than random physical occurrences that individual minds notice.

There is clearly a connection between ecological collapse, our place in nature, nature’s mind, and what is perhaps implied for deep ecology and our relationship to the agency of the more-than-human world. And I recently noticed Matthew Crawford lamenting that AI is beginning to own not just “the means of production” but “the means of thinking” and that the antidote is a newfound recognition of who we are:

We are in for real political turmoil. The establishment is afraid, and rightly so, that the most likely alternative to technocratic rule would be something atavistic. If there is a silver lining in the current confusion, it may be this: without a social class whose material interests are tied to the homogenizing and reductive metaphysics of technocracy, it may become possible once again to entertain big metaphysical questions. We may become open, as the West has not been for centuries, to truths made available to us in the tradition that runs from classical antiquity, through the Hebrew bible and into the Christian teaching. According to this tradition, the human being is something doubly distinct: a natural kind that is oriented beyond itself, indeed beyond nature altogether. Human beings participate in something transcendent, in the image of which they were made. This truth provides a basis – I suspect it may be the only solid basis – on which human possibility may be defended against erasure.

There are tensions here between transcendence and immanence that are informed by debates on consciousness. An emphasis on the dignity of the individual soul and the monotheistic God is not the same as an emphasis on entanglement, postcolonial reckoning, interdependent arising and the virtuality of self. Baptism is not astrology. Liturgy is not meditation. Sunyata is not Maya. We make a big mistake if we assume everyone who senses a similar problem feels called to the same ecology of ideas for the solution. Our challenge is nonetheless to forge alliances with people we mostly agree with on the delusion we have had to endure, and on fundamental matters of value and pragmatism, even if worldviews inevitably diverge.

I share this preamble to show why, given the stakes, I think it’s clearly worth investing some time in understanding this consciousness malarkey.

**

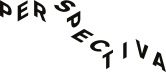

A recent article in The New Scientist indicated 350 theories of consciousness, which are from the same underlying research as Landscapes of Consciousness, an impressive work of collection and synthesis created by Robert Lawrence Kuhn and developed with Alex Gomez Marin.

350 theories? Alex jokes that consciousness theories have become like toothbrushes, in that everyone has one, but nobody wants to use anyone else’s.

The narcissism of small differences creeps in, and people become attached to their specific way of doing things, even when the differences between theories are often a contingent matter of language or emphasis, not unlike the infighting Monty Python alerted us to between The People’s Front of Judea and The Judean People’s Front.

As you can see, the theories are clustered into views that are broadly materialist, including some that are physicalist but not reductive, or informed by quantum theory, or the integration of information. And then there’s a kind of intertidal zone of panpsychism, the new fashion, the surprisingly sensible shoes of consciousness theories; it takes comfort in the familiar physicality of the fabric and sole, while creating some wiggle room for mind.

I’ve always felt that panpsychism sounds cool. Just to say the word makes us feel intelligent. But on closer inspection, the idea that everything has some element of subjective experience, or that every self-organising feature of life has at least rudimentary consciousness, gets a little slippery. For some, panpsychism is merely materialism-plus with mind reluctantly ‘tacked on’; for others, it is idealism-minus, conceding that we need spacetime and physical extension to be outside of the mind for reality to make sense. Panpsychism can even be seen as a form of tacit dualism because it always entails some alliance between matter and mind, with neither collapsing into the other quite enough to separate them to everyone’s satisfaction. And that’s before all the proper dualisms, monisms, and idealisms kick in, all of which have a history. And then there are the juicy theories based on anomalous and altered states, which are like forms of epistemic confectionery.

Dual Aspect Monism is the diplomat of consciousness theories who tries to have its own splendid metaphysical cake and eat it while others watch, claiming to be ontologically monist, but phenomenologically dualist. That means the world is neither all matter, nor all mind (both monist views) and nor is it both (dualist); instead, mind and matter are derived from some even more fundamental quality or substance that cannot be named and could just be ‘reality’, but might be something resembling God or Tao (ontologically monist) that manifests in more ways than one (phenomenologically dualist).

But then there are challenges to the whole schtick, suggesting the inquiry is mistaken in some way, or that consciousness is inherently mysterious and we should get over ourselves. I am eagerly awaiting an ‘Un-theory’ of consciousness by Alex Marin Gomez that appears to say it’s ok to hold one theory one day, and another the next, and that this is not mere lack of resolve but discernment about the limitations of theory, and a recognition that theory is often context or situation specific, and can be a kind of performance or play.

This view chimes a bit with mysterianism, which says, roughly, that just as we don’t expect dogs to understand calculus, because that’s not a reasonable species-specific expectation, there is no particular reason why humans are ‘up to it’ when it comes to grasping the enigma of consciousness. That sounds like a challenge, and I’m intrigued by what amounts to a response, mentioned to me by metamodern groundwater theorist (no really) Professor Marko Cuthbert, channelling Ken Wilber. The suggestion is that normal human consciousness may not be able to understand itself, but that there are forms of spiritual or nondual perception where the conundrum not only looks different, but somehow dissolves. Just as refined perception sees a benign paradox where others see a malign contradiction, maybe the only way to make sense of consciousness and materiality is to bootstrap ourselves into a perspective from which the problem dissolves. In case this risks sounding like a growth-to-goodness fallacy, this process is just as likely to feature radical unlearning as hierarchical development.

**

I have been trying to locate myself within these theories, and I feel as though I am standing on the level above the main concourse of Waterloo Station, looking down during rush hour, distantly inspired by the scene from The Bourne Ultimatum. The theories are like a swarm, but they cluster in terms of hair colour, many hide behind sunglasses, some are trackable through their Gucci bags, a few have extravagant beards, and some identify as Siamese twins. I hope to recognise something, without knowing quite what to look for. Consciousness, is that you?

I have not yet found my stranger in the crowd. But I am invested in ‘The Flip’ as part of ‘The Flip, The Formation, and The Fun’. The flip represents transformation of perspective, and one of the most tangible ways this manifests is in the shift from seeing the world as primarily physical to realising it is primarily or even exclusively experiential. I have not yet found my toothbrush, but in the process of preparing this article, I have had a few major realisations that pushed me towards idealism; though, whether I am in fact more like a panpsychist or a dual-aspect monist, I can’t yet say. I don’t even have a toothbrush yet, and all I can be sure of, when I walk down the street, is that I am a pedestrian.

**

But here’s why I am gradually developing a view of consciousness that is broadly idealist in nature.

The first aha! for me was realising, inspired by Bernardo Kastrup videos and books, that everything we know about the physical world is known through experience, and that we can’t really get beyond experience. This was a shock. That solid table you knock as the touchstone of the external world - sensation is all you’ve got - the experience of knocking the table. That music that’s playing - vibrations? Yes, but all you have is the feeling of the vibes and the hearing of the sound. That pain you feel, yes, the feeling of pain. You cannot escape the fact that all we ever have is some kind of experience, whether through our eyes or fingertips or mind, it is experience all the way down. This is not a decisive point, but it was a penny drop insight. We know the world outside our minds through our minds. Whenever we say: look at that, listen to that, touch that, smell that, taste that, imagine that and think ‘that’s physical!’, in fact, it’s the experience of the physical, i.e. it is experiential. Even the quintessential analytical philosopher, Bertrand Russell, understood this (Human Knowledge, 1948, p. 240):

We are acquainted with the intrinsic character of events only when these events are mental events in ourselves.

I have only recently felt this idea, and I encourage the reader who doesn’t follow to touch something nearby and then notice what you have - a sensation of touch rather than any affirmation that the thing you touched has a physical existence independent of your experience of it.

As the assassin of materialism, Double Dr. Kastrup does a fantastic job. Look at his Philosophical Bond-Villain face up there…He also offers a clear alternative view that he calls analytical idealism. It is analytical in the sense that he feels we can reason ourselves towards it with a mostly abductive (inference to the best explanation) argument. Much of his argument is “what you see is not what you get”. We do not follow through on what we already know from very basic philosophical reflection, namely that what we perceive through the filter of sense perception and prevailing conceptions is not the world as it is in itself. He uses the analogy of the aeroplane cockpit to make this point. What the pilot sees on the dashboard is not for instance, the sky, or the external air pressure itself but a good gauge of it. Likewise, what our mind does is create representations of the world to help us ‘fly the plane’, but those representations should not be confused with what is being represented, which is beyond direct perception. (See chapter three of Analytical Idealism in a Nutshell for the full take down, which is also summarised in the video above).

**

The second aha! moment that moved me towards idealism was grasping just how confected the idea of matter is. We have somehow confused ourselves into thinking that matter is self-evidently real, while mind is mysterious, but it should be the other way around. Matter is, roughly speaking, reality minus mind, and there ain’t no such thing. We think of matter as a solid and reliable generic substance, perhaps visualising billiard balls ever-reducing to the vanishingly small but still present, still solid; all the while not noticing that matter is an abstraction and a kind of charlatan. William James puts it pithily in Principles of Psychology, 1890, Vol. I, p. 146:

Matter is but a name for the unknown cause of our sensations.

I don’t want the case against materialism to look like a strawman argument, because brilliant people believe in it and are defending it. Still, most defences appear on closer inspection not to be materialism as such at all. They either shift the meaning of matter to include mind in one of the many strains of panpsychism, or they smuggle in a moment of hocus pocus in which mind emerges from matter, with the explanatory mechanism looking like a form of well-disguised wishful thinking. I am reminded of Daniel Schmachtenberger’s celebrated fireside talk, in which he speaks about emergence being “the closest thing to magic that is actually a scientifically admissible term.” He describes emergence as a process of attractive forces – phenomena drawn to different aspects of itself - giving rise to relationship – non-random patterns of connection - then to ‘synergy’ – a whole that appears to be greater than the sum of its parts - and then emergence, which is about how that ‘greater’ manifests. I don’t know Daniel’s view of consciousness, and I suspect it is probably not materialist, but when people indicate that mind emerges from matter, it is this kind of ‘magic’ they are referring to. In most cases, however, there is still a major explanatory gap.

Some also see matter and mind as a kind of continuum, with matter as a phase of mind (McGilchrist), or as a kind of habit of nature in Charles Sanders Peirce. Peirce’s view is distinctive and brilliant, and part of a more intricate metaphysics of Quality, Reaction, and Meditation; or Firstness, Secondness and Thirdness, that I do not know well. His view of matter seems to me to be accidentally amusing, though, in the sense that he sees matter as mind that has been kinda busy being creative for millennia before running out of steam and collapsing in a heap at the side of the road. For instance, in his collected papers (1935, Volume 6, paragraph 158) he says:

“Matter is merely mind deadened by the development of habit to the point where the departure from it becomes very rare.”

I’m just going to have a wee sit down for a few thousand years, says mind, and thereby becomes matter.2

**

The third aha! moment, is that in the context of the role of matter in theories of consciousness, I understand better why we should not be shy to talk about quantum theory, which challenges almost every classical intuition we have about the physical world. I am neither a physicist nor a philosopher of physics, so everything that follows should be treated as a kind of gonzo ethnographic report of my own untrained adventure, rather than as scientific fact or even cutting edge philosophy. Over the years I have been skirting around this material, starting on the popular science end a quarter of a century ago, with The Tao of Physics by Frijof Capra, and latterly The Dancing Wu Li Masters with Gary Zukav. Both books say, roughly, that our scientific worldview has matured enough for us to see perennial wisdom in a new light, and that much what is deemed religious or mystical can be seeen, at least analogously, as being supported by developments in our understanding of physics.

We are all looking for foundations, and it can feel validating when you think you’ve found them, even if they don’t look like ‘foundations’ at all. And yet, a few years later, I was pleasantly challenged by Quantum Questions by Ken Wilber (2001), where he tells everyone to calm down, and argues that, almost by definition, there cannot be scientific support for a spiritual worldview. His contention, a variant of the claim that one cannot derive “ought from is”, is that many great scientists are only incidentally mystics, and they are dealing with different aspects of reality, with spirituality concerning the interior, and science studying the exterior.

BUT HANG ON!… Doesn’t that beg the question? I had never really noticed this before. Wilber’s metatheory has a dualist side, even if he’s a ‘dual aspect monist’. From an idealist perspective, Wilber’s AQUAL maps begin to look a little brittle, with the distinctions between interior and exterior and individual and collective breaking down. Perhaps that’s the point - these maps are there to help us navigate complexity, not to disclose the structure of experience in a mandatory way. Even so, after spending a few hours with the worldview of someone like Barnardo Kastrup, the language of ‘interior’ and ‘exterior’ sounds very different. If it is all experiential rather than physical, one would be forgiven for thinking it’s all ‘interior’ but that is not quite right either.

In any case, quantum theory unsettles the ordinary idea of matter to such an extent that we are right to doubt whether the word “matter” refers to anything solid or self-sufficient at all. The picture that emerges from quantum physics is not one of tiny everlasting pellets banging around in space, but of a world that is fundamentally relational, probabilistic, and in important ways participatory. At first blush, those words have a new age hue, but whatever the alternative vision of the world and the words we use to describe it, what is very clear is that what we used to call “stuff” behaves nothing like stuff. So-called particles are not bits of substance with definite positions and trajectories but wavefunctions; mathematical objects that represent not facts but possibilities and probabilities.

A second challenge is that quantum ‘objects’ do not possess definite properties unless something interacts with them to bring those properties about. Position, momentum, spin—these are not attributes the particle carries around with it. They crystallise only when measured. The idea of a self-contained, fully determinate material thing no longer holds. Third, entanglement goes further. When two particles become entangled, they behave as parts of a single system even when separated by enormous distances. The properties of each are defined in terms of the other. What happens here can be correlated with what happens there without any signal passing between them. Einstein found this deeply unsettling, but experiments have repeatedly confirmed it. The classical belief that matter consists of independent units turns out to be an illusion. Instead, the universe is knitted together in ways that defy any simple notion of separateness. Fourth, the measurement problem, dramatised by experiments such as the double-slit experiment, indicates that observation or interaction may be required to produce definite outcomes. The observer cannot be cleanly separated from the observed. This challenges the classical assumption that the world possesses a full set of determinate properties regardless of whether anyone looks. Fifth, the idea of a vacuum—supposedly empty space—is alive with fluctuations, virtual particles that wink in and out of existence, and restless fields that never fully settle down; particles are not fundamental entities, but more like momentary excitations of fields.

Taken together, these five features of quantum theory (and there are others) push us away from a substance-based worldview and toward a universe made of processes. Quantum entities come into being only through interactions; they do not maintain fixed identities through time. Matter, in this sense, behaves more like a verb than a noun, which is why I commend the recent revival of process-relational philosphy, in which Matthew David Segall is a leading light.

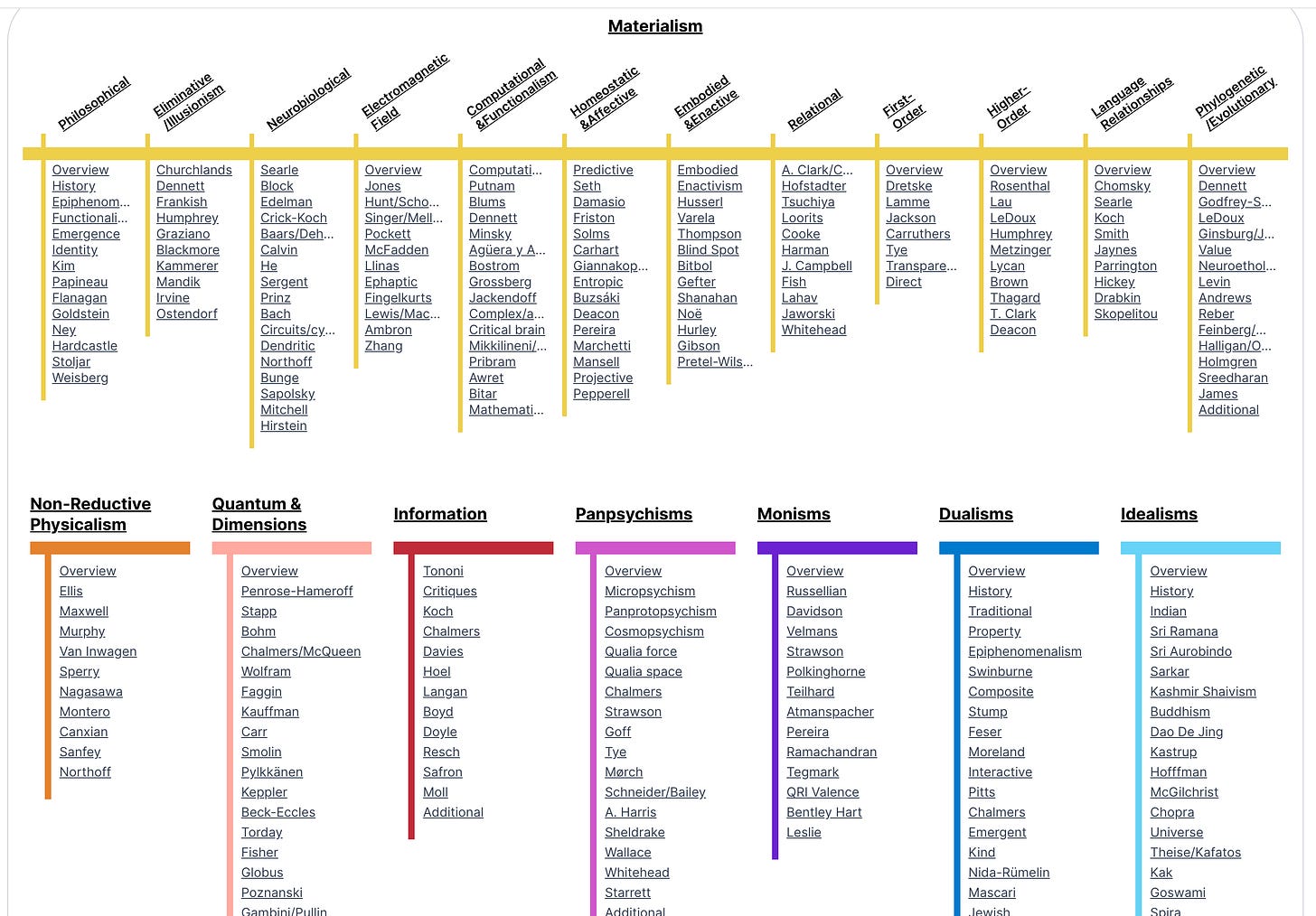

For those interested in articulating a broadly idealist view of consciousness that is informed by Physics (and mathematics) it is worth reading Maria Stromme’s recently published article called: Universal consciousness as foundational field: A theoretical bridge between quantum physics and non-dual philosophy. I have only read this paper once and look forward to revisiting it, but the central conceptual device is the distinction between Mind, Consciousness, and Thought (introduced by Sydney banks) in which the thresholds are wave function collapses. The paper includes this image, which would not be out of place in an Ursula le Guin novel:

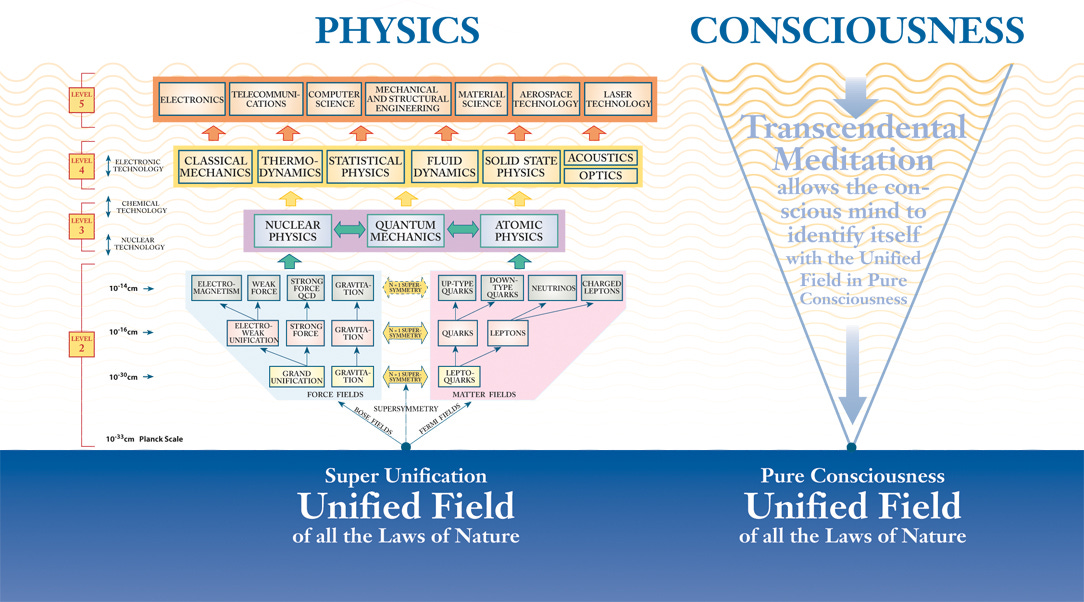

Stromme’s paper looks like an extraordinary intellectual achievement, and I don’t mean to imply false equivalence, but in terms of my own experience of these questions, her paper also reminds me of the ‘Consciousness is the unified field’ arguments arising from the Maharishi World of ‘Vedic science’. I practice TM, and I have applied my mind to its theoretical basis, but I am not qualified to pronounce on its veracity. Images like the one below always struck me as broadly plausible, but difficult to entirely trust due to the connection between a scientific worldview and a particular practice of mantra meditation or vedic sound meditation that had a pre-commercial life as indigenous knowledge, but is now being sold as a trademarked product/service called Transcendental Meditation by an international organisation. (*They would argue this is necessary to protect the purity of the knowledge and that TM teachers are not typically high-earners*).

The overarching point is that we really don’t know what we are talking about when we talk about matter. We think we do, but our folk ontology here is just some notion of physical stuff on a microscopic scale that we can rely on as building blocks for the world, but we know on reflection that there ain’t no such thing - it’s just a lazy habit of thought. I don’t want to overstate this point. There is extension, and resistance, and space and time, and there may even be a physical world, but we need to unlearn the idea of matter as a touchstone. Before I move on, you may have noticed I managed to explore quantum theory without talking about the cat…

**

The fourth aha! for me is that apparently anomalous experiences start to make a great deal more sense when you open yourself to the idea that we are living in a kind of sea of consciousness where waves of meaningful associations come and go and the distinction between past, present, and future becomes blurred. As indicated in my personal post on The Fox, The Forest, and The Frogs, I believe we need to open ourselves to the idea of “meaning without cause”. This appears to be the view of Carl Jung and Wolfgang Pauli on Synchronicity (and perhaps indirectly in David Bohm’s Implicate Order, in the sense that synchronicities can be seen as an explicit-order manifestation of the implicate-order structure, as indicated by David Peat). These arguments are explored Bernardo Kastrup on Jung’s tacit metaphysics. Coming back to the originator of the idea of ‘ontopoeics’, Freya Matthews lays it all out in a book chapter titled Living Cosmos Panpsychism from 2019, where she suggest that these moments of contact, though often unbidden, can also be solicited:

The communicativity of reality, according to living-cosmos panpsychism, is not necessarily a given of our experience but may need to be activated via practices of address or invocation. Responses to such address may be manifested through serendipitous conjunctions or synchronistic arrangements of circumstances. From this perspective, the ‘language’ the world speaks, when it does speak, is a poetic – concretised and particularized – one. For example, in relevant invocational settings, it may take the form of a bush burning on a mountain, a raven participating discreetly in a funeral ceremony, a butterfly alighting on a dead woman’s breast, a message bird appearing out of nowhere to show the way, lightning punctuating a ritual performance with apposite displays.

All such ‘signs’, whether occurring in religious contexts or not, may be seen as instances of a vast poetic repertory, a repertory of imagery, of meaning conveyed through the symbolic resonance of things. It is in such language then that our invocations may need to be couched, since it is in such language that the world is able to respond: it is able to speak things. For things to acquire poetic resonance however, they generally need to be framed within a narrative context, which is why religious and spiritual traditions, and the liturgies which express them, generally rest on and are defined by founding narratives.

In Indigenous societies, invocations are likewise shaped by Dreaming stories. But the efficacy of invocation need not necessarily be confined to either religious or Indigenous contexts. When the living cosmos responds, in person as it were, to our poetic address, in terms referenced to the particular idiom of our invocation, we feel so intimately and extravagantly blessed, so moved and shaken on our metaphysical moorings, that our allegiance henceforth will be first and foremost to this cosmos itself, generally under its local aspect, the place or physical context which provides the lexicon of revelation. Love of world in this sense becomes our deepest attachment. It replaces self-love as the root of our motivation.

Those final two lines are worth sitting with. I am not certain, but I think ‘living cosmos panpsychism’ can also be thought of as a kind ecological idealism. We are back to the toothbrushes again.

The important point, however, is a kind of figure/ground reversal in which the occassional moment of intense personal meaning are not anomolies to be explained away, but active ingredients in the spiritual recovery of humankind, in a historic moment where it really matters what this uniquely human quality of consciousness is about, and how we might make it centrally relevant again.

When it feels like the world is talking to us through vivid and meaningful connections between our psyches and events, we are inclined to explain such connections away as a mere coincidence, because we have been trained to think events in the world arise from material causes, and advised not to indulge in self-indulgence or self-deception. But perhaps consciousness was always here. And maybe our interiority is not a recent epiphenomenon emerging from the relatively obscure notion of ‘matter’ but more like a blessed ringside seat to an objectively subjective reality. And maybe there is a non-causal order, in which meaning prevails. It may be hard for us to grok that, but it looks more plausible when you realise that we are less like meat machines and more like waves within an ocean of experience. In that world, synchronicities not only feel meaningful, but they are meaningful; they are less like errors in perception to be explained away, and more like cosmic data informing an explanation of who we are, and what we have forgotten ourselves to be.

**

The fifth aha! is that David Bentley Hart’s exposition of classical theories of God includes the Vedantic trio: Sat, Chit, Ananda - being, consciousness, and bliss, and I suddenly noticed that ‘chit’ was probably integral to any coherent notion of God, which indicated to me that consciousness and divinity may co-arise.

This is perhaps why Rupert Sheldrake prefers to call himself a panentheist rather than a panpsychist. Perhaps the separation of consciousness and God should be resisted. That’s too big a question for now, but if idealism is partly about the ontology of subjectivity, and there is “something it is like” to be God, then we are cooking with gas, though what we are cooking remains unclear.

The sixth and final aha! is that one of my favourite short stories suddenly felt like a teaching story. The Circular Ruins by Jorge Luis Borges is about a man who gradually dreams another man into existence in the ruins of an ancient temple.

He succeeds, and yet right at the story’s conclusion, just as he is about to surrender to death, he cannot escape the conclusion that he himself, too, is someone else’s dream. The Circular Ruins is a stunningly brilliant piece of writing that includes lines like “No one saw him disembark in the unanimous night…The purpose which guided him was not impossible, though it was supernatural. He wanted to dream a man: he wanted to dream him with minute integrity and insert him into reality…He sought a soul which would merit participation in the universe…” And there are exquisite details about fire, and mud, and rivers, and circles, and patience, but the heart of it is something deeper, revealed in the exquisite ending:

For what was happening had happened many centuries ago. The ruins of the fire god’s sanctuary were destroyed by fire. In a birdless dawn the magician saw the concentric blaze close round the walls. For a moment, he thought of taking refuge in the river, but then he knew that death was coming to crown his old-age and absolve him of his labours.

He walked into the shreds of flame. But they did not bite into his flesh, they caressed him and engulfed him without heat or combustion. With relief, with humiliation, with terror, he understood that he too was a mere appearance, dreamt by another.

I can’t quite explain why, but I now read this story as much as creative non-fiction as fiction. I don’t quite think I am in someone else’s dream, but the idea that “life is a dream” feels more vivid and palpable than it used to. By that, I suppose I mean that the notion that I am somehow living inside another mind does not seem so far-fetched or scary anymore, especially if that larger mind is divine in nature, and shared by everyone else, too.

**

These points all need developing. I just wanted to share where I’m at. Let me close by reflecting on why I think this inquiry matters.

The question of whether consciousness is the host of the cosmos or its guest, the matter of whether consciousness is primary, pervasive, and perennial, or derivative, localised and recent, is not just a fascinating intellectual game. That inquiry directly informs a frontier in human experience: those moments, noticings, and synchronicities when we feel we are in a conversation with the world. As indicated in part one and part two, the idea of ontopoetics is informed by a range of overlapping ideas, articulated most directly by the Australian deep ecologist Freya Matthews, and particularly clearly in a 2007 paper:

Ontopoetics rests on the premise that there exists an inner aspect of reality which is expressed via a communicativity that coexists with but does not over-ride physical causality. If physics is the study of the causal order, then ontopoetics may be defined as the study of the poetic order, of the meanings that structure the inner aspect of being. If ecology has in recent decades defined the first phase of the re-negotiation of our modern Western relation to reality, ontopoetics might be integral to the second phase.

I agree with that last line especially, which is a distillation of the broader idea that the problems of the 21st century are primarily (but not exclusively) spiritual in nature. I have defined the metacrisis more carefully elsewhere, but one way to think about it is that it’s a collective estrangement from forms of the nature, meaning and purpose of life that matter; in which the truth of those things have been falsely rendered, and now need to be re-revealed, re-encountered, and perhaps not re-constructed, but rather participated in more fully.

Ecology - the study of home - is necessary if we are to resist the tragic madness of ecocide, the delusion of an extractive world-system, and to help us all return from our self-imposed exile, or as Latour puts it, to come back down to earth. However, ecology teaches us about ecological niches, and yet does not by itself inform the broadly religious quality of human niche creation and maintenance. Guattari’s Three Ecologies aside, Ecology is not typically concerned with semiotics or hermeneutics and does not speak with sufficient discernment on matters of meaning, manifest in experiences, images, and interpretations. Ecology is fundamentally about relationships, but it is still primarily the world as ‘it’ or ‘its’, rather than as ‘I’ or ‘we’.

To shift register slightly, too much emphasis on the system is displacement, and too much emphasis on the psyche is indulgent. What is enlivening phenomenologically is to recognise the place where system meets psyche and move yourself and others from that point. The place where system meets psyche is enlivening because it reveals the pattern of our stuckness, of our immunity to change, and all the ‘priors’ that shape it. Or to put it in terms of Perspectiva’s seventh of ten premises:

We will not survive the 21st century with literal and figurative firefighting to protect all the things that are burning down - trees, habitats, houses, truth, democracy, attention, peace, sanity. We need a new flame to illuminate a direction that takes us away from the secular theodicy of consumerism through which we compete for status, and vote for insipid governments with necrotic ideas. That new flame, I believe, needs to speak from and to a deeper recognition of the intrinsic value of being human, grounded in a transformed perception of what life is, and (therefore) is about. And I believe any cultural renaissance depends upon ‘the flip’ of seeing experience as primary, primordial and pervasive.

As Zak Stein put it in Education Must Make History Again:

During times between worlds there emerge certain ideas and thinkers that are, properly speaking, without a world. Their work is about creating a new world, by necessity…The focus of work in the liminal is on foundations, metaphysics, religion, and the deeper codes and sources of culture—education in its broadest sense…

And as Bonnitta Roy says in her chapter in Dispatches from a Time Between Worlds:

We are not so much working for greater systemic reach or to identify all the links in an enormous causal chain; rather we need to closely examine the metaphysical operating system of our minds, and participate in the creative emergence of a new structure of consciousness.

Bonnie mentions ‘new structure of consciousness’, and here’s a final thought on that.

Cynthia Bourgeault has reflected on Jean Gebser’s prophetic vision of how consciousness evolves and enters into time. Bourgeault suggests that our challenge is to allow our ‘magic’ and ‘mythic’ forms of consciousness to co-arise with our mental-rational function, such that a new kind of consciousness can arise, informed by what Gebser calls the ‘diaphanous awareness’ of integral consciousness (which has no direct connection with Ken Wilber). This is the kind of mind that is more suited for our times, and that will allow us to ‘see through the world’ in the way we need to. On page thirty of her full reflection, she writes:

While the inner work of us Wisdom and contemplative/evolutionary folks may be to tend our own conscious emergence, I believe that the cultural work we must undertake together is to help REPAIR and HEAL the traditional structures we’ve inhabited so that they can become healthy vessels of the repressed mythical and magical (and for that matter, mental!) structures. My wager is that when this imbalance is corrected, the full emergence of the Integral (so clearly already waiting in the wings) will be its own unstoppable force. We don’t need to race on up to the front of the train in order to reach the station first; we have to make sure that the passengers in all the train cars are well tended and still hooked up as the station in fact rushes to meet the train.

So this is what I am up to here. The moments of deep meaning and encounter in our lives - when we feel something was meant to happen - are intimations of a metaphysical vision that is better suited to the cultural, educational and political challenges of our times. In Gebserian terms, the mythic and magic structures of consciousness still abound, but we don’t take them seriously as equals to the mental structure that liberal democratic power wrongly believes to be epistemically sovereign, and they are manifesting instead as the rebounding of repressed shadows, in the dark arts of falsity and fascism.

So this inquiry into ontopoetics is not just about ‘meaningful coincidences’ as an “oh-how-interesting” talking point - it’ also about repairing and healing the traditional structures of consciousness we are in exile from. When the world talks to us, it does not do so primarily through the mental structure, but through the magic and mythic structures; through the magic-like sense of what Owen Barfield calls ‘original participation’ in which we are fully immersed within the world; and through the mythic sense, informed by Joseph Campbell and many others, that our story animates and is animated by the cosmic story. The mental structure matters too, and so with all due caution, care, and humour, I am wondering what it might mean to make the ‘transformation of consciousness’ we hear about a reality. As part of that responsibility, I am taking synchronicities seriously, not just as signals and totems for our personal journeys through life, but as affordances for reconceiving context, perception, and agency at a planetary level.

Merry Christmas!

**

Let me share what I have researched to give you some idea of why I consider this issue important. I read Bishop Berkeley’s Dialogues as an undergraduate c1997 - a classic text for idealism. I find the opening chit-chat endearing: “That purple sky, those wild but sweet notes of birds…”

I don’t remember any of my Berkeley essays, but a few years later, as a master’s student at Harvard, now 2003, I took a class with David Perkins on Peace, War, and Human Nature, where we were assessed on two pieces of writing we would share on the website. One was about the Kashmir conflict and the partition of India and Pakistan; the other was an essay called “Do we need a transformation in consciousness to achieve world peace?” I looked at some of the heterodox but peer-reviewed research from 1988, indicating that having large groups of meditators near a conflict zone might help reduce conflict - the theory of change was effectively a theory that conflict arose from collective stress, and the presence of advanced (Sidhi) meditators could reduce stress in a sufficiently reliable way that there would be a measurdable reduction in conflict. I then extrapolated to the relationship between consciousness and peace more generally, including a nod to The Global Consciousness Project, which ran out of Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research (PEAR) Lab under psychologist and statistician Roger Nelson. The hypothesis there is that during moments of global emotional coherence—e.g., world tragedies or celebrations, random number generators will show small but statistically significant departures from randomness, indicating some kind of collective mind was at work, and that is indeed what they found.

I hadn’t given theories of consciousness much thought for a couple of decades, but I enjoyed The Flip by Jefrrey Kripal a few years ago, which put me back onto this inquiry. I read all of The Matter with Things before Perspectiva published it, but I recently re-read chapter 25 on Matter and Consciousness, which is exquisite (though the second half is exacting). I also read Bernardo Kastrup’s Analytical Idealism in a Nutshell, and then Decoding Jung’s Metaphysics by the same author. And I read most of For The Love of Matter by Freya Matthews. I browsed The Landscapes of Consciousness site below, and read, hot off the press in November 2025, Universal consciousness as foundational field: A theoretical bridge between quantum physics and non-dual philosophy by Maria Stromme. I also watched lots of videos. The Essentia Foundation’s production of “The Hidden War on Consciousness” with Alex Gomez Marin is good. I lost track of exactly which Rupert Sheldrake videos made the biggest impression, but I listened to his recent lecture on Panentheism twice, his talk with Kurt Jaimungal is edifying, and his conversation with Kastrup is worth seeing, not least for why Sheldrake does not consider himself an idealist.

It’s too much for now, but Paramahansa Yogananda considered matter to be frozen sunlight, and Rupert Sheldrake suggests the sun may be conscious, which might well mean something important, but I’m not quite sure what…

As a blue collar rank and file union activist for 28 years, let me assure you wondering about these topics is wide-spread. While crew in ship engine rooms, I've participated in conversations about scientific assumptions of reductionism, economic materialism, and metaphysical topics in general. We just tended to use the "f" word much more than is usually the case among academics.

Because of a series of intense mystical encounters and other experiences of what I call high weirdness, I became one of Jeff Kripal's correspondents. I've also been in Facebook discussions with Bernardo Kastrup. I own books by close to all of the writers you mentioned. Incidentally, re-reading Wilbur closely became off-putting. He seems to me too sure and a bit of an elitist.

As for "bootstrapping," conservatives and capitalists misuse "pull yourself up by your own bootstraps." It wasn't admonishment about personal responsibility and individual hard work as all that are needed to become successful, but just the opposite--try it! It meant we need each other and was acknowledgement of the reality of structural inequalities.

At 77, a two-spirit and elder, I can say with confidence I know less at this age than I did in my 40s-50s. If forced to pick, I'd opt for panentheism. Maybe dual aspect monism, but it's not quite persuasive. Pantheism seems too close to a form of materialism. It also has the problem of explaining how greater consciousnesses would arise; clearly parrots are more self-aware than pebbles. Therefore not solving David Chalmer's Hard Problem, either. Nor does the New Age talk about energies; I get that's a metaphor for some(thing) we can't quite grasp, but since matter and energy are interchangeable forms, that's another non-solution.

Because of my encounters I decided, despite being raised without religion, to go to grad school in theology in my 50s--maybe the trad religions had some truth to them. Maybe they do. But for me, it was a Procrustean bargain and I couldn't remove enough of myself to fit. Moreover, using the term "God" makes it seem we understand what we're talking about. No way can finite minds, even if pieces of or participants in a whole Mind, fully know an Entity spread across the cosmos and perhaps beyond. Besides, the Christian insistence "God" is all good is a mess. Evil then has to be blamed on some other entity or on humans. Which means whether "God" is a poor designer, not omniscient, or okay with what that bad entity does, She/He/ Them/It is still responsible. Look at black holes and supernovas; destruction (evil?) from the beginning. Even if organizing centers for galaxies and the source of elements heavier than iron we living beings need, any other living beings too close to either are killed. So...??? But I think Carl Jung was onto something with Answer to Job and The Red Book. And I think linking consciousness to time but not to space is worth some contemplation.

One last point. The idea "we" will not survive. Reminds me of a joke I heard in the '60s from a Native reservation relative about the '50s TV show The Lone Ranger. The Lone Ranger and Tonto, his Native sidekick, are surrounded by what appear to be hostile (Red to you Brits) Indians. The Lone Ranger says "We have to fight them, Tonto!" To which Tonto replies "What's this 'we', white man?!" Some of us Indigenes never lost the connection to Earth Mother and to the spirits of animals and plants. Look at the health of our environments. It wasn't because of intellectual inferiority, technological ignorance, or an inability to understand empirical data. It was a deliberate choice.

Hi Jonathon ... You wrote: peace?” I looked at some of the heterodox but peer-reviewed research from 1988, indicating that having large groups of meditators near a conflict zone might help reduce conflict - the theory of change was effectively a theory that conflict arose from collective stress, and the presence of advanced (Sidhi) meditators could reduce stress in a sufficiently reliable way that there would be a measurdable reduction in conflict. I then extrapolated to the relationship between consciousness and peace more generally, including a nod to The Global Consciousness Project, ...

I was one of around 200 (alleged ) 100 UK and 100 US "Advanced (We had advanced a lot of money 🤦♂️) TM Siddhi Meditatirs" who sat in "close proximity" (in hotels) to a specific conflict (The Fall of the Shah in Teheran) and meditated 6 hours a day in hotels ... 1978-79 in Teheran.

In hindsight it feels like a form of service to something larger than oneself ...

Just for the record

I appreciated the essay enormously Bohm floats my boat and you brought many new voices to scan under my radar THANK YOU. Loved the numbered building aha's 👏👏

🙏💙🙏

Rob R³ Running, Rambling, Rob

My personal favourite Bohm quote is:

Reality is what we take to be true.

What we take to be true is what we believe.

What we believe is based on our perceptions.

What we perceive depends on what we look for.

What we look for depends on what we think.

What we think depends on what we perceive.

What we perceive determines what we believe.

What we believe determines what we take to be true.

What we take to be true is our reality.

.... David Bohm

I first encountered the poem / quote in the Epilogue of Perfect Brilliant Stillness by David Carse* on p380. It took me nearly ten years to find a source ...

Quote: In considering the constructed nature of reality, Ricard quotes from a 1977 Berkeley lecture by David Bohm (December 20, 1917–October 27, 1992), in which the trailblazing theoretical physicist offered an exquisite formulation of the interplay between our beliefs and what we experience as reality:

See: https://www.themarginalian.org/2015/09/22/the-quantum-and-the-lotus-riccard-david-bohm-reality/

I tried to explore the Bohm Bohm further

My diagrammatic attempts at unpacking, which I think I shared before are at ...

https://lifebeinglife.wordpress.com/2020/08/16/search-results-and-bohm-maps/

(Originally posted

16 August 2020)

If you scroll down there are four crude maps and an attempt to address the dynamic (trinity) at the heart of the quote / poem

Descending from Reality into our experience creating mechanism where the three way interaction between: (a) perceptions (b) what we look for, and (c) what we think, generates our unique personal history in memory (a) affects (b) affects (c) affects (a) in a dance of perpetual re-inforcement and feedback loops. Then depending on our dominant inner tendencies, ascends in the last three lines leads to the projection of our inner sense making, onto the external world as encountered by the individual interacting with the Actual.

[Note added: 2025-12-16, maybe!]

****