Can we Change our Reality Settings?

Ontopoetics (2): An Introduction to Federico Campagna's Cosmogonies

“…Might it not be the case that change seems impossible, because technically it is impossible? And might it not be the case that imagination, action or even just life or happiness seem impossible, because they are impossible, at least within the present reality settings?”

- Federico Campagna (Technic and Magic 2018, p2)

When we have an issue with our phone or computer, like unwanted notifications, we often hear the advice: “You have to change that in settings”. In the context of ecological collapse and political breakdown, this post considers the possibility that the same injunction applies: we have to change our reality settings. We are not condemned to do the same thing over and over and expect different results if we know exactly what we have to change.

We can meet in illustrious venues with views of the river, preside over ostentatiously large whiteboards, enjoy an array of colourful pens with that mildly psychoactive smell, admire glass bottles of sparkling water that open with a satisfying pop, savour the crispiest shortbread biscuits, and laugh as we relax into beanbags we are not sure we’ll ever get out of. In those arenas, we can allow our minds to roam, and together we can imagine a relatively benign and enchanted more-than-human world. In that fantastic future, we will have peace, plenty, abundant clean energy, democratised finance, wise control of technology, agile governance, flourishing ecosystems, transformative education on every street corner, and meaning on tap. I’ve been in many such events, and they provide solidarity and solace; we all need respite from despair. Yet when these kinds of sessions end, we remain limited in what we can actually begin, because the world outside is not in fact outside after all. The world outside remains inside and between us, and it shapes our sense of possibility, however much we disavow its presence. There is a depth to our inertia that is almost unfathomable, but not quite.

We tend to speak of imagination as if it were untrammelled and free, but a defining feature of our existence is that we are, in fact, trammelled - literally caught in our own figurative nets (our settings). We need some constraints for the world to be intelligible, and to experience freedom, but it helps to realise that our raw material for imagination is always what the world has made us, and what we can make with that depends on how our experience is generated.

I see a parallel here in Carl Rogers’ On Becoming a Person(1961): “The curious paradox is that when I accept myself just as I am, then I can change.” I believe that same paradox applies to the social and political world, where we need to stop political resistance from being a ritualistic reaffirmation of a divisive and deluded reality. Instead, I think the challenge is to allow something like a relaxed metapolitical honesty to arise, where we develop a reflexive relationship to power and to our own power. By reflexive here, I mean something that changes through our relationship to that something; just noticing it can be enough.

**

These challenges have been in mind because I’ve been reading Technic and Magic: The Reconstruction of Reality by the London-based Italian philosopher Federico Campagna (2018), which begins in style:

This is a book for those who lie defeated by history and by the present. It isn’t a manual to turn the current defeat into a future triumph, but a rumour about a passage hidden within the battlefield leading to a forest beyond it.

I’ll come back to Campagna, because there have been rumours about life beyond the battlefield for a while, for instance, in the opening lines of The Bhagavad Gita.

On the field of truth, on the battlefield of life, what came to pass, Sanjaya?1

There are layers of reality here that help to contextualise Campagna’s approach. The ‘field of truth’ is something like Tao, or cosmic dharma, which - importantly - is fundamentally ineffable, but it brings out the itch for some Greek words to eff it, nonetheless. There are aspects of Logos, the ordering principle of reality; Mythos, the narrative grammar of value; and Eros, contact with the vitality of creation, but none of these terms adequately expresses it. ‘The battlefield of life’ is about our challenge to live well, where the question of what it means to be human endures. ‘What came to pass’ are distinct situations and events, including Shakespeare’s slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, today’s news cycle, and the experience of feeling defeated that Campagna alludes to.

Sanjaya, the person asked, is a spiritual visionary, guiding a political leader who is literally and figuratively blind in the absence of such vision. We need such vision today, and in 2023, Perspectiva contributed to a JRF Emerging Futures on visionaries to help address that. For that project, I defined a visionary simply as someone who has good ideas about the future, but more deeply as:

Someone with anticipatory consciousness who can transcend and include the present moment by envisaging and articulating an inspiring form of life and help others to believe in it to the extent that it begins to be ushered into being.

That working definition is not too shabby, but more needs to be said about what transcending and including the present moment might entail in practice. In this respect, I see critique, method, and vision as a necessary trinity (loosely mapping onto the three-horizon model). Critique has words, arguments, and images; method has practices, plans, and procedures. So what does vision have?

Vision has needs, too. But they are of a different and intangible kind. We can speak of the mysteries of source energy and unbidden inspiration, but our socio-cultural dispensation shapes the parameters of what counts as intelligible and inspiring imagination. As many have argued, any communicative context is not just about what is said, but what can be said. And vision does not just pop into our heads, but arises through historical antecedents, social networks, educational experience, technological affordances, cultural precipitation, and spiritual intuition. So in today’s context, the challenge may be less about finding visionaries than cultivating enabling conditions for vision to arise.

Echoing JFK: Ask not what vision can do for you, but what you can do for vision.

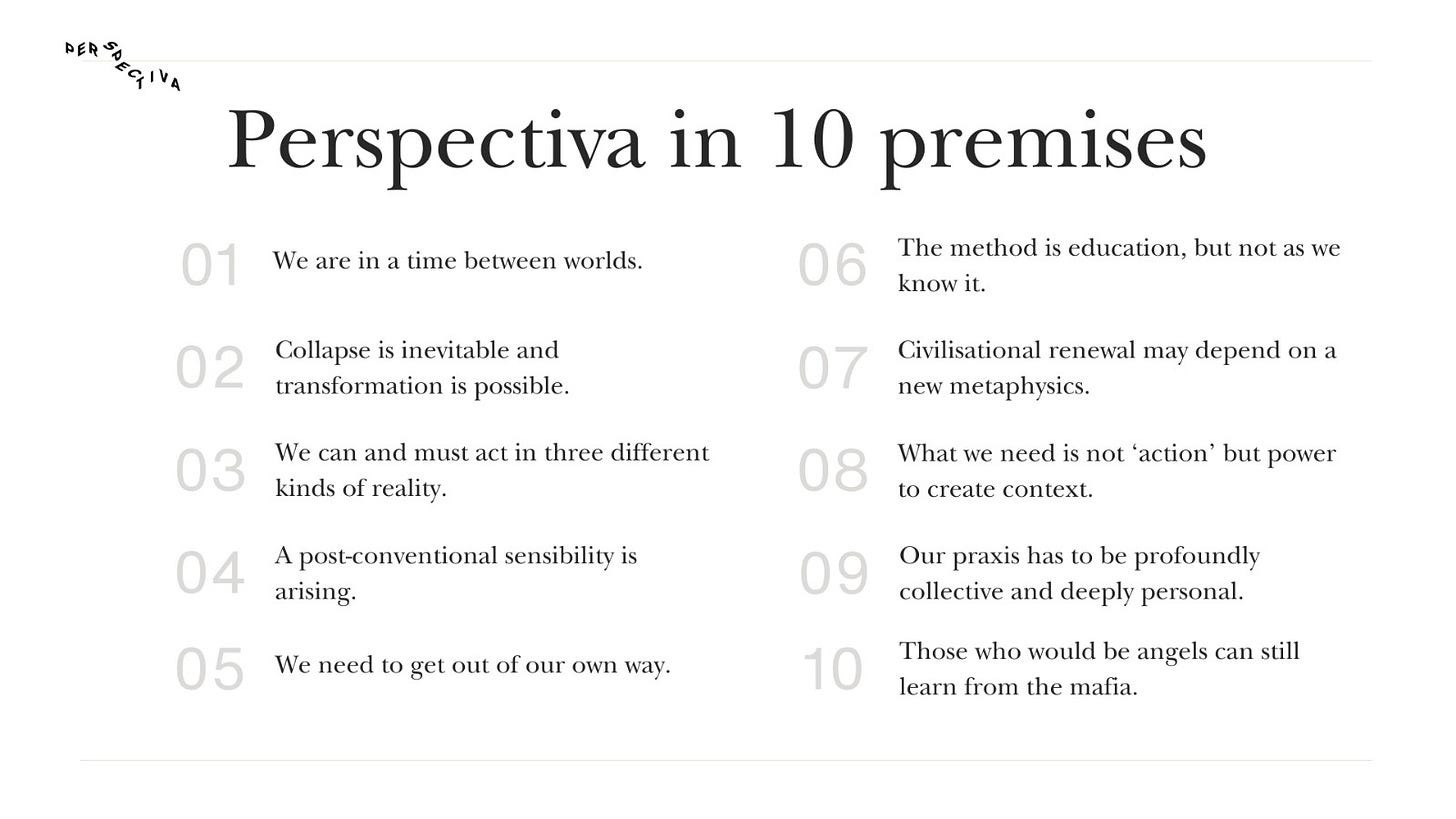

Today, power is concentrated, platforms are owned, attention is diverted, and counter-cultural morale seems low. That’s roughly what is meant by the widely quoted saying that it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.2 This sense of imaginative constraint is partly why Campagna alludes to a sense of defeat for those who most need and seek vision. Our task appears to be creating the intellectual and cultural preconditions and forms of social and spiritual practice required for vision to arise. This is a core feature of Perspectiva’s purpose.

Campagna speaks of ‘reality settings’ as the place to go, and justifies it in terms of the relative futility of other attempts to change the world.

“…Might it not be the case that change seems impossible, becuase technically it is impossible? And might it not be the case that imagination, action or even just life or happiness seem impossible, because they are impossible, at least within the present reality settings? At their core, both questions (point) towards an element within our reality that stood as the ground of the specific cultural/social/political/econonomic settings of our age. Perhaps, it is at that level, that we implicitly define what is possible and what is impossible within our world… it is at that level, that ‘reality’ itself is defined.

- Federico Campagna (Technic and Magic 2018, p2)

For some readers, this notion of reality settings may seem abstract, while for others, nothing could be more important. I’m reminded of the Sherlock Holmes line that once you’ve eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth. Metaphysics is the sub-discipline of philosophy exploring what lies behind appearances, including time, space, causation, substance and so on. This is the field of inquiry where we try to establish what exists and, as Campagna notes, implicitly define what is possible. This idea that civilisational renewal may depend on a new metaphysics happens to be the seventh of Perspectiva’s ten premises.

Metaphysics is not everyone’s cup of tea, however, so it helps to have other ways to look at this challenge. Becoming religious influences your personal reality settings, ideologies are about socio-political reality settings, and spiritual practices of various kinds can shift your experiential reality settings. And there are alternative languages like paradigm (Kuhn) or social imaginary (Castoriadis, Taylor) that some find less forbidding. So it may be a mistake to tie the idea of ‘cosmogony’ too closely to the philosophical terminology of ‘metaphysics’ as if that’s the only way to think about it, but whatever we call it, it is real work, and it matters. Campagna puts it like this:

As the parameters of existence, particularly of legitimate existence, in the world change, so the composition of our world changes - and consequently, the range of possible takes one or another shape, and with it the field of the ‘good’, that is ethics, politics etc.

This notion of ‘parameters of legitimate existence’ is what I am keen to highlight here, because if it were to begin to feel legitimate that we might be in conversation with the world in a fundamental way, as outlined in the first post in this series, “the range of the possible” takes another shape and new forms of previously unimaginable social and political change become possible.

**

I first learned of the word cosmogony - a metaphysical process of world creation, becoming, and destiny- from Campagna. There are several related terms. The ‘gony’ is derived from the Greek gígnesthai, “to come into being”, and cosmogony means world origin, but ‘origin’ is not just a backwards-looking search for a starting point; it refers to our relationship to the creative principle of origination, which is ongoing. The challenge Campagna sets himself is not just studying a world, nor just its starting point, nor how it continually creates itself. Instead, he is interested in how all these things might inform the reopening of futures that currently feel foreclosed. He is interested in forging new destinies, a possibility he believes depends on learning how to generate a new sense of reality. For all the talk of an economy that is ‘regenerative’, our underlying cosmogony may be the real generator. Our reality settings shape how we originate, how meaning is grounded, how our sense of possibility arises, and speak directly to our experience of creative freedom. Today, working with cosmogonies appears to be required for the gargantuan task of redirecting the world’s course.3

**

As a reminder, this post is part of an inquiry into ontopoetics, a broad notion about what it means to be in conversation with the world, defined by the Deep Ecologist philosopher Freya Matthews as follows:

Ontopoetics rests on the premise that there exists an inner aspect of reality which is expressed via a communicativity that coexists with but does not over-ride physical causality. If physics is the study of the causal order, then ontopoetics may be defined as the study of the poetic order, of the meanings that structure the inner aspect of being. If ecology has in recent decades defined the first phase of the re-negotiation of our modern Western relation to reality, ontopoetics might be integral to the second phase.

I begin with cosmogony because it helps to show why, even though ‘the flip’ (Jefrrey Kripal) that I believe is called for, is rooted in experience and is often sudden, the preconditions for it can also be viewed as a reflexive design process, as much as a Damascean conversion. There can be a figurative (or literal) flash of light and a transformed sense of belonging for an individual, but the fallout that matters for societal renewal sooner or later needs to emerge collectively; I don’t think it’s just one person at a time. For those who see this as the challenge, it is our responsibility to understand our existing cosmogony and consider alternatives, including Campagna’s cosmogony of Magic, which I see as a key element of contextualising the intellectual dignity of ontopoetics.

**

We are in the world of worlding here. In The Utopia of Rules (2015) David Graeber famously said: “The ultimate hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.” But read the small print. There is a lot of presupposition in that “just as easily” claim, and not just because the unequal distributions of financial, technological and political power make things difficult. The fly in the web cannot so easily fly away. The spider cannot help but spin. The web itself does not choose what lands on it.

Donna Haraway speaks to related challenges in Staying with the Trouble (2016):

It matters what stories make worlds, what worlds make stories.

It matters what worlds world worlds.

It matters what thoughts think thoughts.

It matters what knowledges know knowledges.

Just as it is said that if the only tool you have is a hammer, every problem begins to resemble a nail, if all you know is the world as you assume it to be, you will look for changes to the world consistent with that model. If we long for a transformed world, we need to understand how worlds are created, upheld, and propelled into the future.

**

One way to think of it is through Bill Sharpe’s three-horizon model, which is broadly about varied dispositions towards the future in the present.

We are all living within a cosmology in Horizon One - the world that is lived, shared, researched, discussed, and above all, maintained. One of the critiques of modernity is its one-worlding quality - a compulsory and enduring first horizon - which militates against alternative forms of knowing, being, and living; for instance, as expressed in the notion of a pluriverse by Arturo Escobar and many others. Horizon one has a history, including a cosmogenesis of how our current world came to be, typically including a Big Bang, planet formation, evolution, pre-history, ancient history, modern history, scientific paradigms, intellectual fashions, and before we know it, we are saying something like: Get off your phone! I’m going to Starbucks, would you like a coffee?

The entrepreneurial frenzy of Horizon Two is different because a relatively small number of people shape the future, while others merely live it. This horizon features the often novelty-hungry and finance-driven work of creating new worlds within our existing reality through cosmopoeisis. However, the extent to which technology or even innovation in general changes the world is moot, especially in terms of what Campagna calls ‘destiny’. As argued previously, there is a recurring and widely recognised pattern of societal adaptation that I call the h2minusvortex whereby prevailing powers co-opt innovation to maintain the status quo, and the French expression ‘plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose’ prevails. It seems to me that vision worth having is ‘H2plus’ i.e. innovation with some endemic immunity to horizon one’s cooptive power.

New visionaries will have the intellectual and imaginative capacity to lift us beyond a fixation with the triage of time-sensitive prioritsing and problem-solving, towards the challenge of working with legacy institutions towards the transition to get towards transformation, which is a completely different world. The sine qua non of the visionary is holding the vision of the transformed world in a way that informs the transitional struggle.

Great work can be done in the first two horizons, and lives can be well-lived there, but if you recognise we are living in a metacrisis, even the best work of the first two horizons does not feel adequate to the task of overcoming systemic delusion, unless you are in conversation with horizon three.

The metacrisis is the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.

The work of transforming reality writ large depends on working with cosmogonies in horizon three, where the imperceptible constants that shape our lives are seen clearly enough for them to be rediscovered as variables to work with. One way to understand the innovative approach towards AI of Vanessa Andreotti and the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures Network, for instance, is that the focus is not so much the world-creating power of new technology in the second horizon, but militating against the risk that technology will serve to reaffirm a pattern of world-shaping power from horizon one that is ultimately reductive, extractive, and destructive. The challenge is to shift this cosmogony through what Vanessa calls meta-relationality, a much deeper grasp of the relationships within and between relationships and how that transformed understanding might shape better ways of being, knowing and acting.

**

Campagna describes our current cosmogony as ‘Technic’.

Technic has many elements or what he calls ‘hypostases’, borrowed from the neoplatonic notion of “that which stands beneath”, emanating from ultimate reality, or ‘the one’; they axiomatic notions that together comprise an overall world system. In the case of Technic, these hypostases are the totalising effects of language (representation as reduction), a fixation with measurement (leading to fragmentation) an ontology of units (as opposed to complex relationships) and ‘abstract general entities’ (as opposed to particular beings).

The ‘reality settings’ of Technic paint a similar picture to Iain McGilchrist’s account of the left hemisphere’s grasp of the world, and perhaps also Harmut Rosa’s view of the world as a point of aggression. Campagna’s key point is that our current cosmogony is actually destroying reality. He sees reality as a relationship between existence and essence, between that which is conceptually captured by language (essence) and that which remains free from capture (existence). He argues, as I understand it, that essence is gradually subsuming existence to the extent that, as essence grows stronger and existence is weakened, the relationship that gives reality its vitality is being destroyed. This tallies with Iain’s view of the left-hemisphere world being a hall of mirrors, and also with fears that LLMs and other forms of AI will devitalise the human psyche.

Campagna’s alternative cosmogony of ‘Magic’ has very different hypostases (chapter three), starting with the ineffable, which naturally we cannot say much about, but I like Campagna’s solution:

We can manage to approach the ineffable as it is ‘in itself’ by moving towards its location within our world. What is invisible to the cartographer might be revealed to the traveller.

He goes on to link the ineffable to the Vedantic notion of ‘atman’, roughly the individual soul that is part of the world soul (Brahman) as that which lies behind our experience:

What I call myself ‘I’, is not ‘I’ but something before my ‘I’ that does so. That is the atman, at once the greatest secret and the most blatant reality.

In other words, our true self is ineffable, and Campagna’s view of reality is that reality is ineffably one but linguistically many.

At the risk of being too brisk, his second hypostasis is the person, which is not to be conflated with the human. Campagna draws on the Latin, Per-sonar, which, as he puts it, in this case means the first point at which the ineffable resounds.

By uttering its first word, the ineffable creates enough of a distance from itself to allow reality to take place…yet, this newly created border of reality verging towards language (this, I), is ontologically dependent and hierarchically subjected to its own ineffable source. Magic’s cosmology thus immediately declares what kinds of reality it wishes to make possible…the space between existence and essence (are) hierarchically ordered.

There is a parallel here with a notion in the Lurianic Kabbalah that Ein Sof’, the infinite, boundless divine, allowed creation not through expansion but retreat, by withdrawing its infinite presence from itself, creating space in which something that is not-God could exist, in an act known as Tzimtzum. Only then could this space receive divine light, which gave rise to all of creation. There is depth here, of course, but the simple message is that it is Godly to create space for others.

The third hypostasis is symbol, which moves a little closer to language, but a symbol always points beyond itself. What Campagna seems to have in mind here is the challenge of language pointing beyond itself, back to its ineffable source. The symbol hypostasis is informed by Jung’s archetypes, but more profoundly by Henri Corbin’s ‘mundus imaginalis’ or imaginal realm as understood by the Sufi thinker Ibn Arabi. To take a shortcut, their perspectives taken together point to an ontologically real ‘place beyond geography’, or Corbin’s ‘place of non-where’, which is also a home we can visit, which leads to the following definition:

The mundus imaginalis is thus at the same time a function of the psyche, of human epistemology, and an ontologically legitimate element within a specific cosmology.

The hypostasis of symbol seems to me to be the proto-language of the place that is not a place, which reminds me of Cynthia Bourgeault’s interpretation of Gurdjieff and the relationship between world 24 and world 48. That cosmology can also be understood in terms of emanation from the absolute, in which the places are all the same place geographically, but very different ontologically due to what is afforded at their level of density or intensification. So, for instance, in World 48, time is linear, while in World 24 it is radial or chiastic; in World 48, causation is sequential, while in World 24 it is synchronous; World 48 is entropic, while World 24 is counterentropic, and so on. It’s as if we live in several worlds that overlap with each other, and we occasionally experience more than one of them at a time, for good or bad (some might argue that Social Media is World 96!).

The fourth hypostasis is meaning, where we are in language, but at the level of syntactic compounds (sentences, paragraphs, poems) where parts give rise to meaning at the level of the whole. The central idea here seems, indeed, to be the centre, in the sense that meaning arises between and through things, and the universe can be seen as a near infinite number of centres of meaning, rather than simply having one spatial centre. So, meaning is where heaven and earth meet in all of us, and also the source of generativity; our own unique centre is our own unique source.

That’s a little brisk, but hopefully close enough, and Campagna ends his Magic cosmogony with the fifth hypostasis, Paradox, which is closely related to Iain McGilchrist’s emphasis on coincidentia oppositorium as if a defining feature of life is the coincidence of opposites. This is important terrain in the context of providing intellectual scaffolding for the idea of ontopoetics, where, as I indicated in part one, the critical question is what exactly is co-inciding, and what it really means to co-incide. It would appear that one of the main ways the hypostasis of paradox shows up is in the self as a kind of achievement whereby individuation relates to the co-incidence, the ‘falling together’, of the ineffable with language, and our conscious and unconscious minds.

From this attempt to summarise Campagna’s alternative cosmogony, I have to say I find it rather brilliant. If we’re not reading closely, it’s just a bunch of abstract terminology in search of God knows what, but if we start to follow the logic, from a sense of political failure, to a search for what is worth trying to change, and then to reality as the relationship between what can and can’t be said, and an emanation from the absolute that takes a very particular shape in ‘Technic’ and ‘Magic’ but in both cases follows a logical process of unfolding, and in each case leads us to a completely different world.

Campagna outlines the essence of Magic’s Cosmogony by quoting Ernesto de Martino as “aiming to restore the conditions in which both the individual and his/her world can regain their presence, and thus can continue in their mutually active and imaginative relationship.”

That sounds like the metaphysical setting for the phenomenology of ontopoetics, and more generally, the language/ineffable frame provides a great tool to make a deeper sense of what it could conceivably mean to be in conversation with the world.

**

I also write on my personal account, The Joyous Struggle.

This is the opening verse of The Bhagavad Gita, in the Penguin Classics edition translated by Juan Mascaro. Alastair compared these opening lines to Jesus saying “I am the way, the truth, and the life”, and while there may be no direct mapping, there is that same sense of life as an interplay of fractals of context and meaning.

To which I would add, inspired by Carne Ross’s forthcoming book on anarchism, it’s easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of the state. And that’s a big part of the problem as I see it. We are so caught up in the question of what will happen to us next and how we might inform it, that we lose the impetus to withdraw consent from the way our lives are framed and shaped by coercive power so that we can move more deeply into generative power.

A mere cosmology is a world that can be studied (eg Tolkien’s Middle-earth, or Ursula Le Guin’s Hainish universe). Cosmogenesis refers to the birth of a world, typically from a starting point but sometimes as an ongoing activity, and cosmopoeisis is about the process of world-creation, which is sometimes proactive. So why cosmogony? The quick answer is that it appears to be best placed to include aspects of all of the above.

Absolutely loving your writing lately, Jonathan. Your voice is so important for equiping us to adapt on the rough roads ahead.

Nicely put together. I trip over the use of "essence" here, since I've always taken the essence to be the unus mundus. Are there other writers who have meant it to be, as you seem to suggest, only that which can be described by language? It's true that to be described, the universe must be, if not divided, at least folded back on itself to afford us metaphors in which to find identities and differences -- that such division or folding may itself be essential to knowing (short of claims to have "pure conscious events" perhaps).

The notion of this sort of perspective being in some sense a vanguard, though.... It reads much like conventional thinking in humanistic and especially transpersonal psychology fifty years ago (when I was in college studying those), and indeed like Huxley's perennial philosophy as he wrote of it decades before that. I liked this stuff then; I like it now. But if we're looking for something truly new, more potent, capable of sweeping the consciousness of our societies, altering the foundations of our co-created worlds, has this stance perhaps been shown to be potent, yet not potent enough? Might some booster be added to its dose to render it fit to the present need and purpose? Or may this be, as an answer, currently a work in progress, tantalizingly close to suitability for wide use if we can but take it a few steps further on its path, as it seems your work to do?