The Flip, The Formation, and The Fun

A back-of-the-envelope plan to change our relationship to what is real, what is good, and how we live.

Everything should be as simple as possible but not simpler, said Einstein, and he wasn’t always wrong.

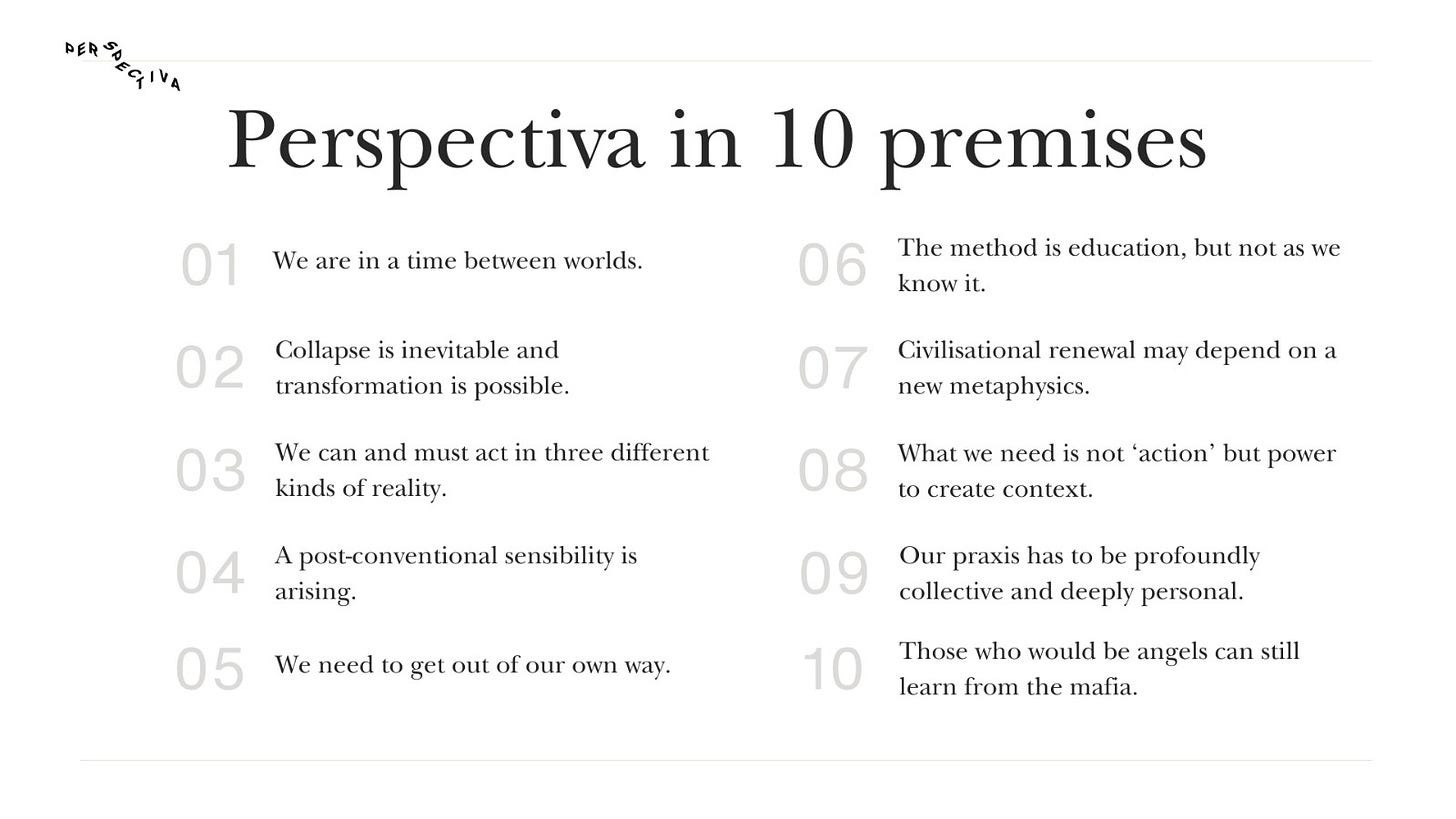

To explain Perspectiva to funders, followers and subscribers, we published Perspectiva in ten premises in June 2023. Those ideas had already informed our work but the positive response to sharing this clarity of context and purpose was encouraging.

Perspectiva’s ten premises are a long-form description of the metacrisis and what we might do about it, which I first wrote about in Tasting the Pickle here, and more recently in terms of the ethics of terminology here. If you prefer video, Living in the Metacrisis in a short documentary by Katie Teague here, and my most recent definition goes as follows:

The metacrisis is the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.

Some people are allergic to the language of metacrisis, and I’ve been thinking of how to distil our rationale to make it even more readily accessible without adultering it. I noticed that premises 1-4 are all a kind of recognition of how things are, 5-7 are all a kind of reorientation and 8-10 are all a kind of reckoning with what follows for the nature of worthwhile action.

In November 2023, I decided that three major patterns of change seem necessary, outlined in The Flip, The Formation, and ‘The Fun on my personal Substack - The Joyous Struggle. This post is a revised and slightly extended version of that argument, and I invite readers to give feedback on the ideas, the language used to express them, and especially what follows for practice.

Next week I’ll be at The Pari Centre in Tuscany, Italy, where I’ve been invited in wonderfully open-ended terms to host a three-hour session on whatever I want, as long as it is broadly related to the subject matter of consciousness(!). A few days ago I decided to talk about these three major shifts and use the generous amount of time allotted to experiment with practice implications. I’m already discussing that approach with colleagues, and I can see a workshop methodology in the making. If, after reading, you have ideas on how to give a room of about thirty people an embodied, enacted, and relational sense of these ideas, to make them more vivid and visceral, please let us know in the comments.

***

In plain language, ‘the flip’ is a change in our understanding of reality, the formation is a change in our relationship to what is good, and the fun is about a change in societal purposes.

The changes are informed by Perspectiva’s founding idea that we live in three worlds of systems (where the ‘fun’ is needed) souls (where ‘the flip’ is needed) and society (where ‘the formation’ is needed) and that any meaningful theory of change has to be premised on the relationship between those three worlds.

There is some bad news. None of these three things will change easily or willingly. The good news however is that these changes are possible, and if they occur in the second quarter of the 21st century, the second half of the 21st century might yet be a time of peace and plenty.

The Flip

First, we need to flip out, as outlined in Jeffrey Kripal’s book called The Flip: Who you really are and why it matters. This point goes beyond Kripal and can be understood more or less broadly. The flip is what people are getting at when they speak of ‘a new paradigm’ or ‘a new way of seeing’ or ‘transformed perception’ or ‘a new social imaginary’. The point is that the scientific and philosophical consensus about who we are is shifting, and it is in our interest to get ahead of the curve. That’s partly what I was trying to do with Spiritualise back in the day, to indicate that political hope may lie far outside of politics, in a shift in the perception of how reality is, who we are, and what it makes sense to do.

The Flip represents a fundamental change in worldview or paradigm, sometimes grandly called ‘a transformation in collective consciousness’ but perhaps more modestly called a major shift in perspective. In more technical terms, The Flip will probably entail a change in our default metaphysics - a term that I think of as our prevailing sense of ontology (what is real) epistemology (how we know) axiology(what we value) and (cosmology) our story of what the world is. That flip could play out in many ways, but I believe a desirable direction is that a critical mass of people gradually come to see consciousness and value as ontological primaries and the world as sacred in ways they don’t currently. The Formation represents a shift in what and how we value that co-arises, inspires or follows from The Flip and is reflected in new metaethics. That means a shift from utilitarianism to virtue ethics; a corollary is transformative education as a modus operandi. The fun represents a shift in metapolitics - mostly a shift from an extractive growth economy built around extrinsic ends to an economy built around intrinsic ends of a cultural and creative nature, loosely (and yes, slightly provocatively) characterized as ‘fun’.

The misplaced presumption of secular liberal atheistic materialism is at the root of our multifaceted delusion called the metacrisis because it precludes the quality of vision, sentiment, sensibility, encounter, and reckoning that are in some fundamental sense spiritual. It does not follow that we invite in old time religion by the back door. As Kripal makes clear, the case for the irreducibility and/or primacy of mind often points towards an uncanny and even disturbing view of reality that is at odds with much of religion. But we do need, as Kripal puts it: “a new metaphysical imagination that does not confuse what we can observe in the third person with all there is”.

The emerging view, which is also a perennial view obscured by the intellectual fashion of the last fifty years or so, is that Consciousness is an ontological primary and an irreducible feature of reality, and so is Value, and that the world is sacred in a way that is not merely rhetoric but more like recognition. There are many nuances and unstated connections that are beyond our scope here, for instance on consciousness alone, panpsychism is not dual-aspect monism, which is not integrated information theory, which is not analytical idealism. The important point for grasping the flip however is that none of them are materialism or physicalism; none of them starts from the assumption that the world is ultimately matter and its emerging properties.

Curiously, nothing follows very directly from ‘the flip’ because the world functions the same way for everyday purposes. I believe it’s important that we do not get carried away with it as a premise for new political initiatives. And yet almost everything follows indirectly from the flip because it shifts perspective fundamentally. The flip helps us to relate to the world less like an overperforming material object and more like a miraculous enchanted relationship; in that new setting, each of us is less alone and we are all called upon to play our part in relation to a whole that has its own beguiling subjectivity and intersubjectivity. The flip is therefore neither a premise nor an axiom, but it is a disposition towards the world, and it entails a cultural correction at the level of intellectual leadership that will have cultural and political implications (not all of them good, which is why we need the formation and the fun too). I believe this flip is already underway, and that it can culminate and become the prevailing view in countries that are currently tacitly materialist, and this can happen in years rather than decades or centuries. This thought gives me hope.

We need to flip partly because without that flip there is unlikely to be epistemic and spiritual renewal, the world will become increasingly unintelligible, and we’ll grow increasingly exhausted. The flip is not a transformation of consciousness as such, but an important precursor to it. There are aspects of the flip in Cynthia Bourgeault’s work on ‘imaginal causality’ and more generally the idea is not one specific thing, but a change in orientation, such that we do not eschew the material world, but nor do we confuse it with all there is, all that is influencing life, or all that we can influence. The flip significantly enhances our curiosity, our appreciation for intrinsic features of life, and our sense of the possible; and in a time of artificial intelligence, the flip may also be necessary to make consciousness, and therefore humans, relevant.

If you’d like to read something to give this matter the requisite scholarly grounding, chapter twenty-five of Iain Mcgilchrist’s The Matter with Things (volume 2) is a good place to start. Iain does not use the word ‘the flip’, and may even disassociate himself from some of the thoughts above and below. However, as his publisher, my view is that the lion’s share of the interest in Iain’s work stems from relief and delight in the recognition that our intuitive longing for something like ‘the flip’ does not come at the cost of intellectual compromise, but rather intellectual renewal, even renaissance.

The Formation

Second, we need a shift in our meta-ethical orientation, from utilitarianism to virtue ethics. That shift might seem really niche! But so much follows from it, not least our cultural logic, and the broad shift of emphasis from a society built to serve economics and a society built around education for higher ends.

Utilitarianism is the view that we judge the rightness of an action based on its likely consequences, and we assess those consequences in terms of their utility, which is something generically useful, valuable, and measurable. That’s a very brisk simplification of a complex body of moral theory, and risks straw-manning (forgive me, I’m blogging) but in all its guises, utilitarianism, at least by itself, seems ill-suited to contending with problems at scale. Partly Utilitarianism is ill-suited to problems at scale because it makes the mistake of confusing what is measurable with what is important, and partly because we cannot track the consequences of actions with any reliability and therefore use it as a basis to decide or to assess decisions. More fundamentally, utilitarianism leads us to what Derek Parfitt called ‘repugnant conclusions’ where what appears to be morally right is often sharply at odds with our moral intuitions. These kinds of concerns don’t seem to have discouraged movements like effective altruism or long-termism, which I believe are dangerous and deluded (though sadly well-financed) views of the world, as Perspectiva has helped to illustrate.

Why does this matter? Utilitarianism is the metatheory underpinning capitalism, and it organizes our political economies and therefore shapes the world. Utilitarianism is the unacknowledged lingua franca of public policy. Utilitarianism is codable and is therefore becoming embedded in artificial intelligence systems. Utilitarianism also takes preferences as given, and has little to say about how our desires arise, even if that’s from addiction or advertising. What we need today, at least in the late capitalist West, is not to satisfy prevailing desires but to try to reclaim our capacity to shape our own desires, and align our desires with our higher purposes and better societal aims than status-seeking consumption. That aim is in direct opposition to capitalist logic, so it seems as the philosophical premise driving public policy, utilitarianism will not help us ‘want what we want to want’ as Frankfurt famously put it. But perhaps virtue ethics can.

There is too much to say at this point because virtue ethics has its technical side in analytical philosophy. Virtue ethics is concerned with the question of what is good, what increasing goodness means, and what it means to grow towards goodness and thereby live well. Virtue ethics is fundamentally about formation being the central project that shapes the meaning of life. Becoming who we are. Collective individuation. All that.

One way to look at it, as Habermas put it, is that Modernity separated the value spheres of truth, beauty, and goodness and our challenge is to find a way to put them back together. What follows is outlined in my essay on Bildung where I take inspiration from Jon Amos Comenius, a Czech philosopher and theologian who lived from 1592 to 1670 (and declined the offer to be President of Harvard University). He is considered by many to be the father of the idea of universal or democratic education.

Comenius’ genius lay in grasping that since learning is as natural as breathing or eating or sleeping, education should be seen as an aspect of nature’s formative process; and since nature is often experienced as sacred, and we are part of nature, an organism’s lifelong disposition to learn is the wellspring of meaning and purpose in life. A healthy society that is attuned to nature and other sources of intrinsic value depends upon making this educative process the axis upon which society turns

This point is deepened and developed in Zak Stein’s contention that Education is the Metacrisis: Why it’s time to see planetary crises as a species-wide learning opportunity.

If the flip is about relating to reality differently, formation is about growing through and for that relationship.

But how does all this play out politically?

The Fun

Third, political leadership now calls for ecological reckoning, and that means helping populations contend with the discomforting truth that indefinite growth on a finite planet is delusional. We all need to find ways to tell the truth that brings people with us. That ‘bringing people with us’ is where the fun comes in. The problem is that the language of degrowth and even post-growth is totally uninspiring. I forgot who said it first, but if we are going to wean the world off the teat of growth or even just consumerism while continuing to meet the needs that consumerism meets, we are going to have to ‘throw a better party’. Or as Emma Goldman put it: “If I can’t dance, I don’t want to be part of your revolution”.

This is not a trivial point! It is not naive to think that the future needs to look like fun, in fact, it may depend on it. And that’s because we need an attractor that is strong enough to draw us out of our immunity to change, and our entrapment in capitalist logic.

For a while, I kept the door ajar to other ideas, but I now believe that beyond the elixir of wishful thinking, there is no viable and credible way to mitigate climate collapse that does not entail reducing aggregate energy demand. That premise means mature economies need to have overarching policy objectives that are not tethered to indefinite economic growth and the financial instruments that rely on it. There are many powerful sources to support this point. A recent lecture by Nate Hagens is well worth your time, as is a paper in Science rigorously questioning the assumptions of Green Growth. Any please read whatever you can by Tim Jackson. There is an understandable madness to indefinite economic growth but it really has to stop. The following paragraph from Jackson’s most recent book, Post Growth (p150) really hit home:

A conundrum faces us here. Those who want change tend not to be in power. Those who hold power tend not to want change. The possibilities for any kind of change depend on the distribution of power coded into the rules of the state. The mercy of the state depends inherently on its mandate. The mandate forged by western democracy is a very particular one. Political power is uncomfortably tied to the delivery of economic growth.

The challenge is to depict a socio-political arrangement that is not inherently oppositional, but rather for something attractive and galvanizing. I don’t know what this is yet, but I have noticed some people now speak of the care economy, and that’s a step in the right direction. Personally, I don’t think the right language form has been born yet, and that’s because what we need is some existential creativity and prefigurative culture that helps bring prefigurative politics into being.

I believe much of the language and much of the practice of prefigurative politics may have to come from the young and be adopted by the old, and I believe that can and will happen soon.

So here’s the outline case: The bad guys are materialism, utilitarianism, and indefinite economic growth. The good guys are the flip, the formation, and the fun.

Here’s how the counter-attack plays out.

On the metaphysical front, we flip. It becomes normal to see the world as enchanted and it looks moribund to think otherwise. We work for that through contemplative practices of various kinds, and innovations in spiritual practice, but also just intellectually and steadfastly.

On the metaethical front, we form. It becomes ridiculous to think that what we want is simply a given, and we actively work to clarify what is worth wanting. We work for that educationally, broadly conceived.

On the metapolitical front, we have fun. Economic growth looks increasingly delusional, while growth of the soul or spirit looks increasingly normal. Speaking of economic growth as a panacea will gradually become taboo, just as homophobia or racism were once normal but are now taboo. We work for that through prefigurative culture, informed by existential creativity.

So there we have it, my back-of-the-envelope plan.

The plan is all a bit rough around the edges, perhaps absurd, and it’s neither exhaustive nor exclusive, but the flip speaks to the work Ivo Mensch especially is undertaking on innovations in spiritual practice, the formation relates to the work our Managing Director Kylen Preator has been doing to strengthen and develop our publishing arm and courses behind the scenes, and the need for ‘the fun’ inspires innovations in Communitas being developed by Michael Bready.

So it’s a relief to have one more answer ready for the recurring question: What does Perspectiva do?

We work to bring about the flip, the formation, and the fun…

I was an ardent reader of Stewart Brand's Co-Evolution Quarterly back in the '70s. He championed long-termism (which I take it you're against), as well as cautions about the absurdity of exponential growth in production of energy and consumption (which we agree with) -- even an early warning the Gulf Stream Atlantic circulation might collapse. He promoted both "Small Is Beautiful" as well as, with The Well, one of the earliest online communities. And he was a great fan of Bateson's ecology of mind. What's now going by "degrowth" was the hippie dream back in the day, along with a great flowering of spiritual inquiries. Brand was subsequently discouraged, beautiful as all this dreaming was, that so little seemed accomplished to realize it.

What can we learn from that earlier wave, and its failure to successfully scale to a larger cultural and economic transformation? Part of the problem may have been painting with too broad a brush. We need, in the short term (and quickly!) growth in certain sectors. We can't just step back from technology -- as toxic as so many of the tech bros are. As a small example, degrowth arguments often focus on the cost of lithium extraction as a reason not to quickly go to electric vehicles. Fair enough, except there are now sodium-based batteries among the many alternatives to lithium. Salt is cheap and abundant. Putting capital into such material transformations requires a large dose of capitalism. Reducing the political power of evil capital (e.g. the fossil fuel industries and their investors) requires producing superior returns for good capital. We need a lot of growth in science and technology -- and that new technology rapidly deployed -- if we're to survive in our new, Anthropocene niche.

One more contrary observation: The primary political threat in many nations stems not from materialism, but from regressive spiritual claims, particularly those based in nationalisms, ethnic identities, and fundamentalist preachings. If the nationalists and fundamentalists in Europe, Asia and America were removed from their respective political arenas we'd all be far surer of steering away from the shoals of the metacrisis. Broadly, there are kinds of spiritualism which are worse than mid-century modern flavors of materialism.

Milton's Paradise Lost describes the tragedy of a previous generation of spirits being supplanted by a new one. How sad for the Gods of antiquity! Are we in a similar transition now, of needing new spirits, new religion, respecting the Abrahamic traditions for taking us this far, and now moving on to something better, something essentially more capable of a hopeful -- and fun! -- future?

Jonathan, your Pari Centre opportunity and your invitation to us are both wonderfully juicy.

I am especially intrigued with your design challenge: To advance ideas for how to give a room of about 30 people an embodied, enacted, and relational sense of our ideas about consciousness — to make these ideas more vivid and visceral.. I thank you for the invitation.

My half-baked thoughts on what I’d do with your opportunity:

Ask the participants to take several minutes in silence deliberating on this question — ‘Given the ‘community' (of place and/or purpose) most important to you, imagine how its culture (its shared patterns of beliefs and actions) would be different if its members where 10X more conscious of their individual/collective choices, and of the consequences of those choices.

Form into trios of participants who know each other least well, and share whatever initial thoughts have emerged for depicting that new culture. The trio task is simply to hear each other in a way that is generative.

Back in total group, harvest comments from individuals on what insights are emerging for them — about content and/or process. Do this popcorn style. No need to hear from everyone.

Go through the same individual reflection time, trio time, and total group harvesting — but this time focusing on the implications of what they are learning from this experiment.

Now, given this rich ‘warm data’ experience, you, Jonathan, can feed back what you’ve been learning from them, and using their language/insights, bridge into your ‘Flip, Formation, and Fun’ framing in a way that they can easily embrace.

Finally, open the floor to Q&A,

I appreciate that I’m projecting my experience/biases on you and your opportunity. Hope it’s a helpful projection. I’d be delighted to help co-evolve the design if this ‘warm data’ strategy happens to interest you.

Blessings, BillVeltrop@comcast.net