We are the World?

What 'The Greatest Night in Pop' reveals about our unintelligible 'We'.

I feel moved to write about a famous pop song called We Are the World, mostly because the essence of metacrisis is that we are not the world.

Or rather, in this world, there is no such We.

I share the thoughts below in preparation for a discussion in tomorrow’s Leading from Confusion online event at 4 pm UK time.

At first blush, the song looks like schmaltzy, low-brow, synthetic music awash with eighties hairstyles and naive lyrics so it all amounts to EPIC CRINGE for the sensibility of 2024. However, through a recent documentary (see below) I have learned to love the magical way the song came into being, I hear it differently now, and I wonder if it might have something to teach us, particularly about collective agency.

But first the problem.

Could it be the case that the problems we think of as economic, political, technological or spiritual may all in some fundamental sense be problems of our grammar too?

More precisely, are we struggling to make sense of our plight in a way that informs constructive action because we are obliged to invoke a We that does not exist, and talking as if it does evokes widespread dissonance, which saps our morale?

Maybe.

This ‘We problem’ is endemic partly because it is hidden within our language. As I have shared previously, I believe the following three things might be connected:

The intractability of collective action problems, especially climate collapse.

The preeminence of English as the world’s Lingua Franca, especially online.

In English, ‘we’ is almost infinitely ambiguous. Our language is fairly unusual in not having ‘clusivity’ i.e. the distinction between the inclusive first person plural pronoun, We, and the exclusive first person plural pronoun, We, can only be established by context.

On the first point, here’s my reflection on working on the climate crisis and the metacrisis which explains why we are so stuck. One key feature of our stuckness is our confusion about collective agency at a planetary level and our inability to solve major coordination problems.

The second point is empirical in that we know there are roughly 1.5 billion English speakers, followed closely by Mandarin, Hindi, and Spanish. But the power of English goes beyond mere numbers. The English language remains preeminent for historical (colonial) reasons, and it has become the language of international business, the internet, international treaty negotiations, and popular movies and songs.

The third point is more complex and relates to the charm of We Are the World. I don’t have the capacity for serious linguistic scholarship, but I find it intriguing, troubling and exciting that there might be something significant about the structure of the English language that makes it particularly poorly suited to addressing today’s pervasive collective action challenges.

Parlez-vous Français?

*

In all the ways it matters - perceptually, epistemically, ethically, spiritually, ecologically, sociologically, technologically, economically, and politically - the world has little operative unity. The institutional problem is that we don’t have effective global governance; the UN has mostly failed to secure peace, prevent famines, or avert ecological collapse.

More fundamentally, most individuals don’t experience the vedic self-recognition of ‘I am that I am’, in Sanskrit सो ऽहम् or sohum; we don’t tend to identify with the world as a whole in all its non-human and cosmic dimensions unless we’re having a mystical experience, or taking psychedelics.

More prosaically, we don’t tend to experience people suffering in other parts of the world as if we are suffering. There is indeed empathy, compassion, heroic NGOs, and generosity, but there is also geographical and cultural context, mental and emotional limits, moral distance, and personal priorities. At the moment, I find this selective care painfully evident in the context of Gaza.

If we are the world, why are we not preventing famine and genocide?

If we are the children, why do we allow our governments to send weapons that lead to thousands of children losing their limbs and their parents?

*

I’ve written about the underlying issue before in Forgive Yourself for speaking on behalf of the World (some of which is included below) and in The Impossible We which includes the following extract:

Many progressive visions of the future are premised on heroic assumptions about widespread cooperation and shared interests aligning at scale. There is abundant good will and ingenuity in the world, no doubt, and I believe in giving our better natures every possible chance. Still, the only pathways to a viable future for humanity that seem credible to me now are those that acknowledge the enduring realities of self-interest, competition, conflict, defection and corruption. I have been feeling this point acutely in relation to ecological collapse in particular, where ‘we’ are called to act. The core problem is the absence of any locus of shared power to generate cultural sensibility and policy coordination commensurate with our collective action challenge, and to see it through in the context of widespread political divergence and resistance. That indicates a different pattern entirely may have to emerge, but for that to happen the words we use will have to pre-figure it better than they do today.

Another way of putting it is this: I sympathise with those who believe the future of the more than human world depends on a spiritual breakthrough, mass metanoia for eight billion people, but I also feel that this view is spiritually bypassing on stilts.

While spiritual realisation and maturation are a critical and necessary part of the response to the metacrisis, any spiritual transformation that might have a material impact at scale is not likely to be evenly distributed, and it’s not likely to happen quickly. This is partly why Perspectiva grounds itself in the relationship between systems, souls and societies. ‘We are the world’ has more credibility when you recognise that our world is three worlds that co-arise and influence each other but don’t collapse into each other. Our souls may long for unity with the world, but our society tests that unity and our systems militate against it.

There are many aspects of the metacrisis, which is why I call it a multi-faceted delusion. What I want to focus on here is that we often talk as if there was a ‘We’ who could find and know itself and coordinate to respond to calls to action, rather than a We that is defined as much by war as peace, as much by othering as belonging, as much by rivalry as friendship, as much by broken institutions as functioning ones, as much by corruption as by leadership.

This is not a counsel of despair, but a critical part of the challenge we need to see clearly, and music offers a lateral angle to think it through.

*

Perspectiva recently invited Greg Thomas to inform and inspire our Music and the Metacrisis inquiry led by Michael Bready.

As part of a broader description of the principles of the Jazz Leadership Project Greg mentioned the Netflix documentary, The Greatest Night in Pop, as an example of an ‘ensemble mindset’. The film is about one night in 1985 when the US pop stars of the time came together to sing a song to raise money for a famine underway in Ethiopia in 1985. The official trailer is here:

The documentary is wonderful!

I particularly enjoyed the ‘leave your ego at the door’ sign that welcomed the singers, Bob Geldof setting the scene with his gruff gravity of purpose; he didn’t quite say “Just give us your f***ing money” but that sentiment was there in spirit. Bob Dylan looked like a fish out of the water, but then there was a beautiful moment when Stevie Wonder (who is blind) helped him find his way back by mimicking Dylan’s voice. Bruce Springsteen sang wonderfully despite losing his voice, somehow finding it about ten miles inside his diaphragm - in fact, it’s only when ‘The Boss’ first sings ‘Weugh aaaargh the World’ that the song began to feel like it matters (see a clip here).

I also enjoyed all the things that didn’t happen, including Madonna not being there because Cyndie Lauper was there, and apparently(?) it had to be one or the other, the Swahili lyrical improvisation that was abandoned, and Prince not, after all, showing up to play the electric guitar - that very idea was wonderfully incongruous. I also admired Lionel Ritchie as the smooth operator keeping the show on the road. “Hello, is it me you’re looking for?”

If you also ‘leave your ego at the door’ it’s a joy to watch how they all ‘got it together’. Some people walked out, some never came, some got tired, some got drunk, but they achieved the aim, partly because they had a shared aim. Can we say the same thing about the world as a whole?

*

The film has depth too, illustrating some major philosophical themes Perspectiva is contending with. Three ideas in particular come to mind: metamodernism, collective individuation, and ‘The Unintelligible We’.

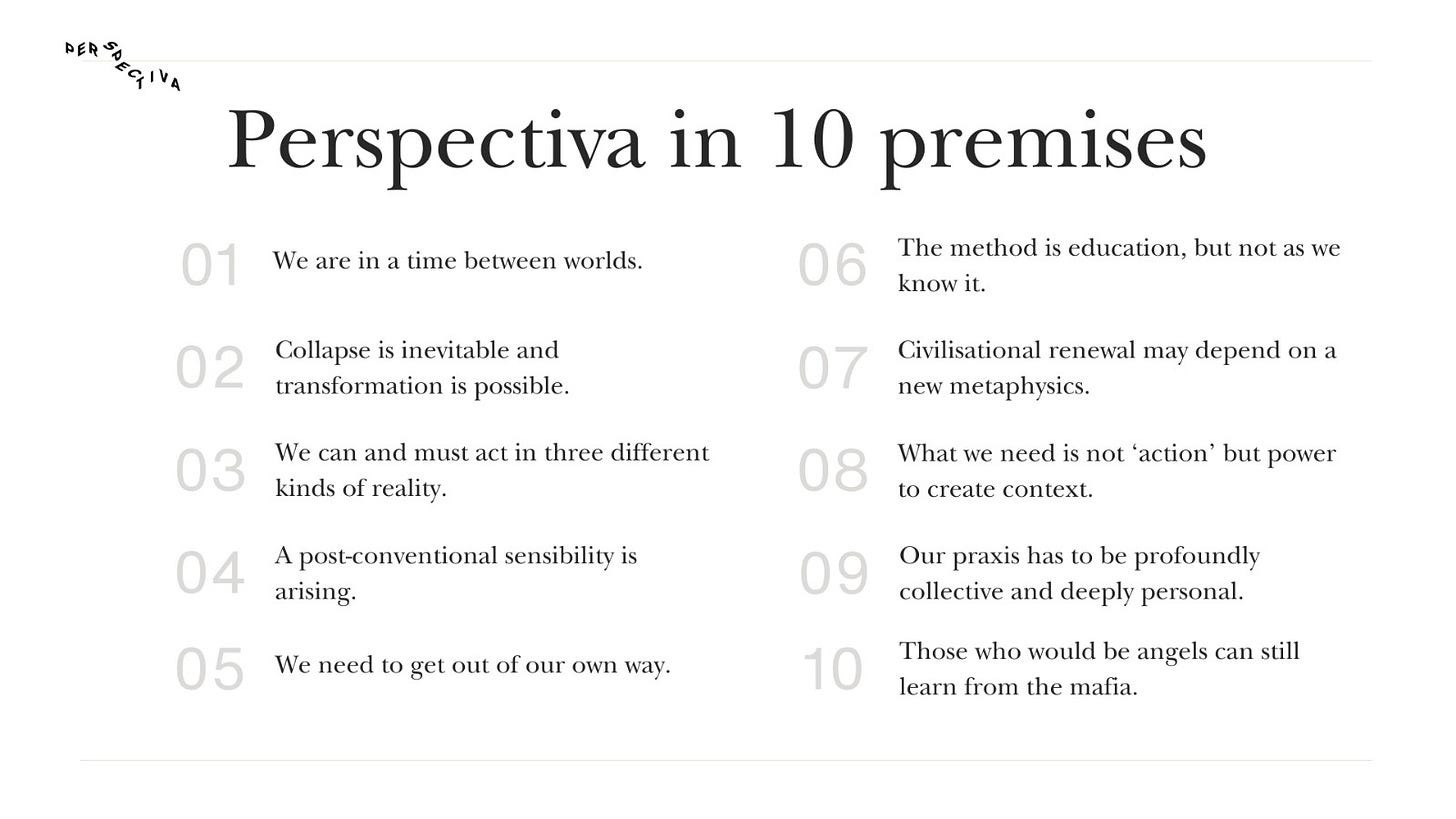

In terms of Perspectiva’s ten premises, these ideas correspond respectively to some of the substance behind ‘A post-conventional sensibility is arising’ (04), Our praxis has to be profoundly collective and deeply personal (09), and ‘Those who would be angels can still learn from the mafia’ (10). I’ll consider them in turn, with my focus on the latter.

Metamodernism: The Greatest Night in Pop is metamodern in a revealing sense.

At first blush, ‘We Are the World’ is just a cheesy pop song featuring a bunch of big egos who may or may not care about the cause they profess to sing for. A Cynic would say they were sent there because they didn’t want to be left out, or because their agents told them it would look bad for their brands if they weren’t there, and the lyrics at first blush appear sentimental and unoriginal. And yet, we can see the partial validity of those observations/critiques and move beyond them.

If you are new to metamodernism, it’s a whole conversation, but my essay here from 2021: Metamodernism and the Perception of Context is the best I’ve got.

The key line in this context is from Dutch cultural theorists, Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker, in Notes on Metamodernism in 2010:

Ontologically, metamodernism oscillates between the modern and the postmodern. It oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naïveté and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity.

Metamodernism as a cultural sensibility allows for a perception of context and meaning in which the singers can be both vain and noble, selfish and generous, competitive and collaborative, performative and authentic. Mixed feelings and paradoxes are the emotional and analytical signatures of metamodernism. The Greatest Night in Pop is not just a film about a song. On the creative principle of ‘show don’t tell’ the footage and commentary tap into major human themes including collaboration, growing into the challenges of our time, ‘heeding a certain call’ (an opening line of the song), the bittersweet evanescence of kindred spirits sharing a never-to-be-repeated moment together, and the moral and aesthetic significance of music’s mass appeal. There is also a tribute to excellence. When you watch and listen, everyone showed up for those short moments they had to make their unique presence felt, and it’s wonderfully put together - the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Consider the lyrics:

“We are the world, we are the children. We are the ones who make a brighter day, so let’s start giving. There’s a choice we’re making. We are saving our own lives. It’s true we make a better day, just you and me.”

You can read these words as trite and trivial, and you may feel Michael Jackson and Lionel Ritchie wrote them for their catchiness rather than their existential depth. And yet to a metamodern sensibility, ‘there’s a choice for us’.

We are the world: Yes, in the context of famine, the challenge is to relinquish geopolitical morality and feel another’s suffering as our own regardless of where the afflicted are.

We are the children: Yes, we projectively identify with those most tender and helpless, and try to inhabit their suffering and feel it as our own in a way that motivates us to allay it. Or as Tina Turner puts it in the song: “We’re all a part of God’s big family”. Cheesy, yes, and yet, is it not more fundamentally true?

We are saving our own lives: Yes, in the sense that spiritual salvation may be connected to getting beyond the illusion of the separate self, and a recognition that we are ultimately one people. Genus Una Sumus as they say in Latin, and they’re not entirely wrong.

The singers or songwriters probably didn’t feel all these things, or mean all these things. Yet the metamodern choice is to feel all of this simultaneously and err on the side of perceiving the good, the beautiful and the true, filtered in this case through a particular kind of creative and commercial constraint. You can choose to love certain moments, choose to admire people, choose to be grateful, and you can feel all that while still smiling at how ridiculous it all is too.

Collective Individuation

I believe the film also reveals something about collective individuation, which is broadly about finding our unique contribution in a context defined by collaboration. Here is a clip of me speaking about that idea in Living in the Metacrisis by Katie Teague:

I thought of collective individuation in the context of the song because it was striking how distinct the voices were, and I loved how nervous each of the singers was about exactly how and when they would deliver their lines. In Dylan’s case - “the original vagabond” as Joan Baez once called him, he was clearly struggling, but what finally came out was so quintessentially his own, delivered in a way that only he could do it, and that arose from the collective context and purpose. “That wasn’t any good”, he said, but everyone around him was enthralled.

Last, but by no means least, the song title, We are the World, begs the question: Are we really? At the heart of the song, and therefore the documentary is the gap between ‘The Aspirational We’ and ‘The Political We’ that we are obliged to live with, and in that gap, we are confused because our natural language is unintelligible.

The Unintelligible We

Clusivity is a grammatical distinction between inclusive and exclusive first-person pronouns, also called ‘inclusive we’ and ‘exclusive we’. Our inclusive we specifically includes whoever is being addressed, while an exclusive we specifically excludes the addressee. This means English effectively has two (or more) words that both translate to we, one meaning ‘you and me, and maybe someone else’, the other means ‘me and some other or others, but not you’.

So ‘We are the World’ could refer to the fifty or so people huddled into a room in Los Angeles to record a song overnight in 1985, but that’s not how we hear it. And yet some of the cringe we feel is precisely because of doubts about whether the exclusive We of the superstars recording the song could credibly speak for the inclusive We that they profess with so much performative passion to care for. There’s a performative contradiction directly arising from ‘we’, and not for the first or last time.

*

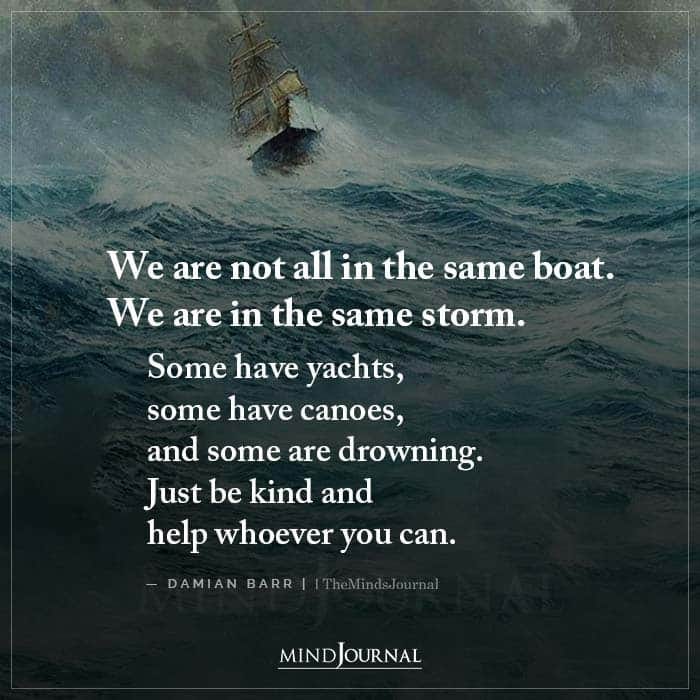

A simple statement by Damian Barr elegantly highlights the problematic nature of the elision between the inclusive and the exclusive we.

We are not all in the same boat (the inclusive we does not apply). We are in the same storm (the inclusive we applies). Some have yachts (‘we have yachts’ is an exclusive we).

There is a deeper and related problem. The promiscuous nature of the inclusive We leads us to conflate our challenges.

Climate collapse is ‘caused by humans’ which means ‘we’ caused it, and yet a study by Climate Majors in 2017 found that just 100 companies are responsible for 71% of global emissions (there may be an updated study or a sharper way to make this point). If those 100 companies were to speak from their exclusive we, they could claim responsibility and act upon it, but instead ‘we’ - not ‘them’, feel obliged to address it. It’s never that simple, because there is some complicity in our engagement with these companies, but the underlying point is sound.

The point is that ‘Humanity’ is rarely a meaningful unit of collective agency, so ‘the inclusive we’ is typically off the mark. And yet we can only specify an exclusive we by getting political, which means moving from ‘all of us’ to more specific and contested moral demands. This is the other problem of the generic and unintelligible We, which is that it acts as a kind of camouflage, a place to hide within, and it lacks the kinds of moral and political commitment we seek to elicit on the other side of collaborative inquiry at The Antidebate.

*

What a predicament! Our collective fate depends on a collective that is not there.

I believe this kind of problem may be a good illustration of the mental/rational mode of consciousness entering its deficient phase, and it highlights the ‘irruption’ of relatively efficient aperspectival ways of knowing that visionaries like Jean Gebser prophesied; views of the world where ‘I’ and ‘We’ and ‘You’ and ‘They’ are altogether more co-arising and entangled.

With those thoughts in mind, as training, consider the following statements and ask yourself if they are inclusive or exclusive or both.

Gens Una Sumus - Latin Motto (We are one people)

We the people of the United States… (First line of US Constitution)

We will fight them on the beaches. - Winston Churchill.

We are the first generation to feel the impact of climate change and the last to be able to do anything about it. - Barack Obama

We children are doing this to wake you adults up. - Greta Thunberg

The point of sharing these examples is to show that unless we stop to think about it, we barely notice the different ways that we is being used, and the inherent ambiguity of the term is part of our predicament. It helps to realise that an inclusive, democratic we (we the people) and global we (humankind) is presupposed in questions like:

· What do we need to do to address climate change?

· How might we save democracy from itself?

· How can we guide technological innovation in a way that benefits everyone?

This kind of language is innocent enough, but it is also maddeningly insipid. There is a profound absurdity here, and once you get the importance of this point it won’t leave you alone.

The mostly unreflective way we use ‘we’ in our discussions of societal direction leads us to ignore localised conundrums, varying perceptions, competing interests, and power dynamics and language obscures the kind of work that needs to be done.

I believe a figure/ground reversal is called for, in which there is a shift from assuming our collective perception, understanding, and interests of the world are a stable vantage point; while the figure or situation we look at together is what remains in question.

We should reframe the challenge so that we see it the other way around, namely to see the We in question more clearly, and to prioritise acting on that. Consider:

· How might the reality of incipient climate collapse be conceived and acted upon in ways that help us transform the We that has failed to prevent it?

· How might the institutions and norms of democracy be strengthened in ways that help to forge a We that is worthy of the ideal and not one that is destroying it?

· How might technology best be designed, owned, regulated, and perhaps even in some fundamental sense dethroned, to foster the kind of We that makes a good society possible?

Better, no? These feel more like generative questions to me. This shift in perspective is part of what I mean in Perspectiva’s ten premises by ‘democratising hyperagency’.

*

To take our preeminent collective problem as an example, the main limitation of the idea that we face a climate emergency is that there is no ‘we’ as such to address it. The We that wants to say there is an emergency is not the same We as the We that needs to hear it, and the We that needs to hear it has several different ideas about the nature of the We that should do something about it.

More generally, there are competing tribes, perspectives, interests, and factions in the world, and perhaps there always will be. Spending time in Sarajevo as part of my Open Society Fellowship was particularly useful, because it revealed how easily and tragically war can arise when a collective sense of We-ness shatters into lethal shards of them and us. At almost every level of analysis, from sclerotic global governance to quarrelling spouses, we appear to lack sanctified mechanisms to resolve what kind of We we want ourselves to be.

Perhaps spiritually we are one, or could be, but politically we are many, indeed for many how we decide to demarcate our ‘we’ is the fault line of politics. As the infamous Nazi jurist and theorist Carl Schmitt put it in The Concept of the Political: “Tell me who your enemy is, and I will tell you who you are.”

That idea risks turning toxic, but our ‘enemy’ can be relatively conceptual like ‘greed’ or ‘capitalism’ or ‘delusion’ or ‘the metacrisis’, and since politics is about our felt sense of the operative collective, it is worth thinking about what we want from We.

The appropriate scale for ‘we’ as a unit of action is the critical question, and it’s an urgent one too, at a time of global collective action problems where the presumptive global we is clearly not a viable unit of action. This is where ideas of ‘polycentric governance’ or ‘Bioregional Earth’ or ‘the global commons’ or ‘cosmolocalism’ become relevant.

Dougald Hine told me in a personal exchange that whenever people travel and converge for conferences of various kinds, he said, the question invariably arises: ‘What should we do?’ And yet there is usually no ‘we’ in the room that is capable of coordinated action because they are all away from their contexts and networks where each of them may more readily establish units of action, and that recurring confusion wastes precious time.

To take an example at a larger scale, we need to keep most oil and gas reserves in the ground and virtually all coal in the ground to give us a fighting chance of staying within the relatively ambitious 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. There’s a compelling case for pursuing that global objective if you are one of the thousands of inhabitants of Tuvalu or any other low-lying small island state with non-amphibious humans who simply wish to live above water.

However, if your political remit is to do something about energy poverty affecting millions of families in a coal-rich part of rural India or China, you may see things differently. Likewise, if you are a rapidly developing African country seeking to catch up with Western living standards you may notice that a lack of an international airport places you at an economic disadvantage. Then it won’t look obvious that ‘we’ should not build more airports.

*

While it is forgivable to invoke We-ness - it really is! - because it’s baked into natural language, a critical part of ‘the work’ today is to resist the trappings of the generic and unintelligible we. I think it’s ok to feel underwhelmed and disappointed whenever a major public intellectual speaks about what we need to do when they don’t also specify the contours of the operative we - I feel that’s part of their job today.

“And when I say we…” should become a familiar qualification.

And yet, this could easily get tedious too.

If we are to be ‘as wise as serpents and gentle as doves’ on this point, that means calling out the problematic We at those times when it is the heart of the matter, but also to be kind enough not to be pedantic, and recognise that we have little choice but to use it in ambiguous ways. Are we clear on that? 🙃

For now, I recommend watching the documentary, and listening to the song with new ears.

We are the world! (Are we the world?)

We are the people! (Are we the people?)

We are the ones who make a brighter day! (Are we the ones who make a brighter day?)

So let’s start giving! (What would it look like for us all to start giving?)

In tomorrow’s Leading from Confusion at 4 pm UK time, I plan to speak further about all this. It’s a free event, so sign up and let’s see if we can make the unintelligible we more intelligible.

We need you!

🙃

Bye for now,

Jonathan.

Thank you for your writing and for recommending the documentary, Jonathan. After yesterday's Zoom session, I found myself reflecting on the significance of the word "we". Despite its frequent use in my work for a non-profit organization, I never fully feel it. Even when I write it, there are moments when it seems to carry a sense of isolation.

The concept of "we" is something I rarely grasp entirely. Perhaps it's due to the current tumultuous state of the world and my country. However, during yesterday's session and again in my “contemporary” dance class, I experienced a profound connection to this collective individuation you mentioned. Maybe.

Although I'm not particularly fond of sports, treks, or yoga, attending these classes with strangers since the pandemic has allowed me to experience the essence of "we" in a beautiful and strange way. I haven’t become friends with any of the people I have been in the class, neither I found the need to become one because it is strange way, I felt connected to them and I was just enjoying the moment so beautifully (I guess, like a similar feeling when I’m part of a Dharma sharing in a Sangha).

Yesterday's session, coupled with the insights from Perspectiva, provided me with a renewed perspective on this collective consciousness, perhaps what you referred to as "collective individuation" (I think this is how you called it? Sorry if I’m confusing the words).

To truly understand this concept, I believe I must first feel a sense of freedom, followed by vulnerability, and eventually a sense of belonging. This process may have been what allowed me to perceive the "we" more consciously.

As I pen these thoughts, I'm aware that they might come across as somewhat idealistic. However, I'm convinced that just as my thoughts evolve, so too does my physical being. Perhaps we often overanalyze the concept of "we", and perhaps we only seek to acknowledge it when it becomes necessary.

I'm writing these words without overthinking, embracing the opportunity for open expression.

Today, I took a break to watch the documentary, and it exceeded my expectations, particularly towards the end with Dylan's active involvement. Hermoso.

I wonder if incorporating activities like singing, dancing, and painting into future sessions could provide a holistic approach to exploring the concept of "we".

Combining these forms of expression with dialogue and introspection might offer a deeper understanding of our collective identity.

Thank you once again for your insightful writing, Jonathan. Your contributions greatly enrich my work.

Thanks for this thought-provoking piece and equally stimulating discussion today. It only struck me afterwards that there is a very McGilchristian way of framing this. The abstract "we" that either doesn't say what it means or resorts to generalities like "we the people/workers/faithful etc" is a left hemisphere artefact. It's either deliberately instrumentalising and manipulating its audience, or it's just deluded (a lone scribe on the internet proclaiming what needs to happen for the world to change, without the agency to make it happen). Real agency requires understanding who, specifically, is going to do whatever it is. Seeing people specifically rather than in categories is what the right hemisphere does because it has access to embodied experience and relationality, which is always between real flesh and blood people rather than abstractions. Your piece has prompted me to take more care to avoid the trap of talking loosely about what "we" should do, and be as clear as I can about whom exactly I'm thinking of.