For a long time, I felt the question: “What makes a good leader?” could best be answered in the Scottish vernacular: Awa’ an bile yer heid! (“Please be so kind as to go away and boil your head”).

I have been wary of the idea of leadership. I know there are many ways to lead and that almost everyone can lead given the chance. I admire leadership when I see it in others, I have been inspired by many great leaders, and there are exquisitely subtle ways to lead, many forms of leadership are inherently collaborative, others are paradoxically all about allowing others to lead, and so on. I get it.

There’s no need to demonise leadership.

But still. Perhaps due to my Scottish egalitarian roots, I have found it hard to shake the idea that there is something irredeemably egoic about leadership. It seemed there was always an awkward status claim lurking in the idea somehow, some insidious aristocratic remnant claiming absolute legitimacy, some stealthy martial logic about who gets to divide and conquer, some fusion of charm and coercion that commands cultural attention while doing capitalism’s bidding. Then there’s the veneration of leadership as a gateway drug to the tyranny of the strong leader, and all that that means politically, historically, and tragically.

You get the idea. I’ve been ambivalent about leadership. But then, as the euphemistic saying goes, leadership came into my life. A few months ago I noticed that maybe I had become…wait for it…drum roll…wait for it…

A leader?

It was a bit of a shock. I noticed that things had happened and were happening to me but also because of me, and that far from shining a light in my face and saying: What do you think you are doing? Life was actually encouraging leadership.

It feels both too vain and too brittle to list examples of leadership here, but I noticed it in some aspects of my chess life and writing life that appeared to have enduring value for others, in my work on spiritual sensibility and climate change at the RSA, in my OSF Fellowship, in podcast and event invitations, and in some aspects of parenting and community life. But mostly I noticed it through my day job at Perspectiva, the organisation I co-founded, and have been leading for the last seven years. After a joyous struggle, Perspectiva appears to be here to stay, and it is coming into its stride now with a good team, a viable financial situation, a clearer sense of purpose, and things to be proud of and to look forward to. There is always luck, but I’ve been asking what, if anything, I’ve been doing to help along the way.

I started thinking about leadership more favourably a few months ago when I was invited to speak at Bonnitta Roy’s Pop-up School (great leadership!) Bonnie is a remarkably insightful person, and I don’t say that just because she has been involved in some capacity with Perspectiva’s work for several years now. She invited me on to talk with her students about how being a father influences my work, which was a distinctive and welcome proposition. After one answer I gave, Bonnie said to me, in front of the group:

“The thing I have noticed about you Jonathan, is that you lead from your confusion.”

Gosh, I thought. So that’s what I do.

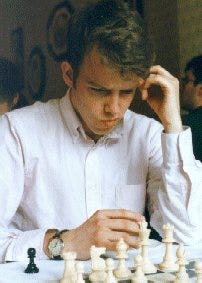

And no wonder! My unique selling point in a civil society context is that I am a Chess Grandmaster and three-time British Chess Champion. Chess has been a huge part of my life since I was six years old, and here’s a press cutting from (*looks down from a great height*) 1987 when I was about to turn ten:

I know many people who seem significantly ‘brighter’ or ‘smarter’ in terms of speed of comprehension and processing power, and many others who are far more knowledgeable. So it makes me wonder what exactly I bring to the table.

People imagine that chess expertise might make me more strategic than most, but actually, it makes me more confused than most. Hopefully in a good way. Becoming good at chess gave me intellectual confidence not in spite of the confusion it fosters but because of it, and life felt confusing for lots of reasons, including my brother and father developing shcizophrenia, as indicated here.

I wrote about the challenge of figuring it all out in my memoir about what becoming a chess Grandmaster taught me about life. The following distillation didn’t impress the marketing team at Bloomsbury, so this listicle never really saw the light of day, but I do believe each of the following things, and they have shaped my sense of meaning in life.

Concentration is freedom

It is the mattering that matters

Our autopilots need our tender loving care

Escapism is a trap

Algorithms are puppeteers

We need to make peace with our struggle

There is another world, and it is in this world

Each of these ideas is a whole conversation, and together they are a whole book, but you may notice they are all somewhat enigmatic and perhaps even deliberately confusing in spirit (which is probably why the marketing team didn’t like them). I’ve shared a few more photos just for the hell of it, because this is the first time I’ve really felt my chess life and Perspectiva life really connecting and it’s weirdly thrilling…

Chess is the struggle against error. Stephen Fry, for instance, calls chess ‘ludicrously difficult’. To be a chess player is to feel that it is normal to make mistakes, mostly because you can’t avoid them, no matter how good you get. So what does it take to become a chess Grandmaster? For most of us, it means spending large chunks of our childhoods getting confused by chess positions for hours on end, enjoying it, and coming back for more the next day. In fact, chess players succeed only when they successfully strive to be slightly less confused than their opponents. I’ve written before about chess as an elaborate pretext to give people the delicious experience of concentration but the same could be said for the only slightly saltier taste of confusion.

I have always been pretty honest about my lack of understanding, and have some of the qualities of an auto-didact who keeps on asking until some sense of inner conviction arises, or at least clarity about what is unknown or unknowable. Chess played a big part in my formation, but I also grew into this love of confusion early in my first year at Oxford University. I had been struggling with some details about the demand curve in microeconomics and was socially distracted by my new student life, so that week ‘learnt helplessness’ came naturally. I told my tutor, Tim Jenkinson, that I just found it all a bit confusing. He replied that confusion in a general or apathetic sense is a kind of laziness, but confusion about particular things is a sign that you are paying attention, and teachers are often delighted to be asked about hard-earned confusion. This! This bit here. This is what I am confused about. This simple distinction between generic and particular confusion was a kind of revelation.

Ever since then, I’ve been hunting for my confusion.

Annie Dillard captures the spirit of that hunt:

“Why do you never find anything written about that idiosyncratic thought you advert to, about your fascination with something no one else understands? Because it is up to you. There is something you find interesting, for a reason hard to explain. It is hard to explain because you have never read it on any page; there you begin. You were made and set here to give voice to this, your own astonishment. "The most demanding part of living a lifetimes as an artist is the strict discipline of forcing oneself to work steadfastly along the nerve of one's own most intimate sensitivity." Anne Truitt, the sculptor, said this. Thoreau said it another way: know your own bone. "Pursue, keep up with, circle round and round your life....Know your own bone: gnaw at it, bury it, unearth it, and gnaw at it still.”

― Annie Dillard, The Writing Life

I identify with the line: “…the strict discipline of forcing oneself to work steadfastly along the nerve of one's own most intimate sensitivity.” I am sure it can be understood in other ways, but I read it as saying: befriend your confusion. Perhaps this is my version of Donna Haraway’s injunction to ‘stay with the trouble’.

I am not totally sure yet what it means to lead from confusion, but I decided to ‘own the compliment’ as it were, and create a communal podcast where we find out together what Leading from Confusion could mean. I hope the idea might catch on!

A few days ago I noticed my post: Inner Development Goals on Trial had gone down well with a wide range of people and I thought: that’s it, that’s what I do well. Just as a chess player knows which questions to ask of a position and withholds his assessment until it feels like the questions are either answered or are getting more refined, I can lead a critical conversation without picking a side. Because I rarely feel I belong on either side, or even see the sides as sides - that’s what chess does for you too; there are always two sides, but there are inviolable rules, some underlying objective truth of the matter, and ultimately there is only one position, just as there is ultimately one reality, though many perspectives on it.

If you’re curious, and how kind of you if you are(!) a similar sense of benign confusion is present in some other writings like Tasting the Pickle, The Impossible We, what I call ‘successful underachievement’, and in Prefixing the World. In such cases, what I feel, I think, is a playful quizzical tension co-arising with a deep sense of mattering and the responsibility to get things right. That kind of phenomenology of confusion characterises much of the chess experience. I suppose it would make sense that if I lead from anywhere, I lead from that place.

So much for me coming to terms with leading, but what exactly is confusion?

“The origin of thinking involves some perplexity, confusion, or doubt. Thinking is not a case of spontaneous combustion.” - John Dewey, How We Think, 1910

“The thing about democracy, beloveds, is that it is not neat, orderly, or quiet. It requires a certain relish for confusion.” Molly Ivins, American humourist.

I share these quotations here because confusion generally gets bad press, and yet it shouldn’t. Confusion is associated with a sense of being lost and feeling vulnerable, but in my experience, it’s more like a spark that gives hope for a fire when a fire is needed. Confusion is a kind of internal data that helps us to better attune to the world. To be confused is to be stimulated, hunting when hungry for elusive epistemic prey.

The word confusion has been in use since around 1300. ‘Confusion’ stems from the Latin term for ‘pouring together’ and conveys the idea of too many things mingling that we feel ought to be separate. The literal meaning of con-fusion is something like 'with (discomforting) togetherness'.

But isn’t that how life feels today? It’s as if, as the recent film title puts it, that we are living with Everything, Everywhere. All At Once. In a time of abundant information from millions of sources on a variety of interconnected issues, confusion is entirely normal. In fact it's the new normal. As Tom Peters puts it: "If you are not confused, you are not paying attention." Or as Irene Peter put it, "If you are not confused, you are not thinking clearly."

The case for confusion might be perennial, but I suspect it is particularly strong today. To wish away confusion or offer false or premature clarity is part of the multi-faceted delusion that characterises our metacrisis. If you want a glorious blast of confusion I can recommend Layman Pascal’s post on Apocalyptarianism, which includes the following line:

“Our ice caps are rapidly melting. There are huge reserves of greenhouse gases that will accelerate global climate destabilization if they come to the surface. Meanwhile the Amazon rainforest — still being deliberately burned — is outputting more carbon than it absorbs. Oceanographers point to simultaneous acidification of the seas and an imminent tipping point for cascading die-offs among marine species. At the very same moment, we are building artificial intelligences, self-driving cars and flying killer robots (lethal drones). Our pocket computers are monitoring us and using special algorithms that deliberately erode attention, break up social bonds and generate addictive stress. We can design the genetics of babies in laboratories. The location of nuclear weapons is getting harder to track. Natural and artificial pandemics are circulating. Deepfake technology means that “audio, video and photographic evidence” proves nothing. At least one of your online friends is a piece of software. At least one of the social groups important to you was created by a distant cybernetic troll farm that deliberately wants to radicalize you. Our democratic legislatures are unresponsive to the will of the people. Wild animals are already full of microplastics and strange hormones. Everyone is taking multiple mood-altering drugs. You can 3D print guns that can’t be detected by airport security. The tools for making bio-weapons are spreading. The most beautiful places in the world are constantly on fire. We are moving to make settlements on Mars. Computers can defeat us at all games. And, according to the Pentagon, UFOs might be back in the picture…This is NOW.”

Layman notes that the question for “a good apocalyptarian” is not: Will there be an apocalypse or not? The new question is: How do we live under the conditions of the apocalyptic mood?

Maybe we have no choice but to lead from confusion.

I like Layman’s verve, but one can also see the centrality of confusion more prosaically in the questions we have to ask that cannot be answered. One way of framing the challenge of the metacrisis is that it’s a kind of hidden educational curriculum about society reconstituting itself by finding its way back to first principles and then out again into a viable world. In this respect, building on the work of Zak Stein and also outlined in Tasting the Pickle, Perspectiva sees five fundamental questions in play today:

Intelligibility – what’s going on, and how do we know?

Capability – do we have what it takes to do what we need to do?

Legitimacy – who gets to say what we should be doing and why?

Meaning – what ultimately matters and how do we live accordingly?

Imagination – what does a viable future look and feel like?

These questions need to be continually asked as a way of keeping our planetary context in mind, and reminding ourselves of the deeper issues that lurk within everyday conundrums. Still, these are living reflexive questions that cannot really be answered definitively, and perhaps shouldn’t be. In fact, they remind me of the cryptic advice from Ursula Le Guin in The Left Hand of Darkness:

“To learn which questions are unanswerable, and not to answer them: this skill is most needful in times of stress and darkness.”

With that metacrisis context in mind, today's challenge is to keep asking the unanswerable questions, but also to reduce shame about confusion and begin to illustrate what it means to be skillfully confused. When Salvador Dali said "What is important is to spread confusion, not eliminate it" I can’t be certain what he meant, and it might have had something to do with an unsuspecting rhinoceros or a melting clock, but I think he meant that confusion is where inspiration comes from. Einstein for instance said, "I used to go away for weeks in a state of confusion."

One approach to ambient confusion is 'sensemaking', which is now widely theorised and can be understood as an antidote to the kinds of naive problem-solving that fail to adequately consider context (and thereby offer false solutions that cause unintended consequences). And yet while sensemaking looks like a social practice that responds to confusion, it has some risks and limitations too, because it is mostly about taking flight from dissonance and other discomforting feelings that often contain unexpected gems. As Bonnitta Roy might put it, it fails to realise that while ‘the signal’ is important, so is ‘the noise’, because the noise is where the latent potential is. We should not be too quick to associate sense with rightness, nor clarity with success. In light of the complexity of the world, there is a case for becoming more familiar with the experience of confusion, getting better at tolerating it, and even learning to love it.

A recent article in The Conversation describes confusion as “a signal of a cognitive impasse” which often leads people to turn away or move on, but should instead act as a cue to struggle for just long enough to actually understand something, even if it’s not the entire phenomenon on play:

“…In new media environments, complex ideas and concepts are often presented in a documentary-like fashion: slick, fluent, engaging, and entertaining (*TED talks come to mind-JR*). Increasingly online videos routinely explain complex processes with striking, easy-to-follow animations, accompanied by dulcet, highly scripted narration. The ideas presented feel like they make sense at the time. But if the ideas do not challenge us in a fundamental way, they might not be being processed deeply enough to lead to any lasting learning. Such environments may lead us to have a false level of confidence in our understanding of complex concepts. Glossy, high-production value resources have been shown to give people an inflated sense of understanding.”

All of which is to say that comfort with confusion is central to the art of learning. The point is not to stay confused forever, but to allow yourself to feel confused for long enough to shift some cognitive structures to allow you to see, feel, and do more than you previously could. The developmental angle here is Piaget’s theory of schemas, assimilation, accommodation, and equilibration. The details of that theory would divert us now, but the heart of it is this: the experience of disequilibrium is the sign that an organism is called upon to change not just what it knows, but how it knows, which often means to grow in some way, but can also mean to simplify.

A deeper academic paper presents confusion as an ‘epistemic emotion’ that gives rise to a ‘noetic feeling’ i.e. the metacognitive feeling of an embodied mind looking at itself. (This paper builds on a prior finding that facial expressions associated with confusion are extremely common and they are not experienced (‘valenced’) by others as being positive or negative.) I was particularly struck by this line towards the end of the discussion on noetic feelings:

“Even if we can decide to abandon inquiry when feeling confused (given other needs, desires, and pragmatic factors such as time pressure), the feeling of confusion encompasses a spontaneous inclination to launch the more demanding cognitive strategies required by the not-easily-feasible task.”

Exactly that! The feeling of confusion encompasses a spontaneous inclination to launch the more demanding cognitive strategies required by the not-easily-feasible task.

Is there a better ‘not-easily-feasible task’ than contending with the metacrisis? And do we not need all the help we can get in ‘launching’ our more demanding cognitive strategies?

These thoughts on leadership and confusion, and how I might best be of service at the moment led me to take Bonnitta’s comment that I lead from confusion not just as an observation but also as an invitation. So my main contribution to Perspectiva’s new community offering is to offer regular sessions on something I am confused about, and work with anyone who shows up to get greater clarity on what exactly we are confused about and why.

At the moment I am confused about what many others are confused about, like why exactly history has created such an intractable conflict in the Middle East, what exactly the threat from AI is supposed to be, and what exactly ‘we’ might do about it.

But I’m also confused about things that are a little more niche, like what is the relationship between the moderate flanks and radical flanks of the climate movement and what follows for meaningful ‘action’ on climate.

I’m confused about what is meant by post-metaphysical spirituality, and how it chimes with the widespread claim that we need a new metaphysics. I’m confused about what is meant by ‘the feminine’ and what it would mean for the future to be relatively feminine. I’m confused about whether or not this period of time can or should be called a new axial age, and what follows from that. I am confused about whether or not modernity is really ending, if the expression ‘a time between worlds’ is really more than poetry, and how confident we can be about that.

I am confused about how to understand the relationship between climate change and AI as major civilisational threats. I’m confused about whether we have one civilisation or several and what it would mean to say both in the context of a so-called multi-polar world. I’m also confused about whether the self is real, and if it is both real and unreal, what do we mean by ‘both’. And so it goes on.

Starting soon, I will host regular (approximately fortnightly) sessions with the Perspectiva community called 'Leading from Confusion' which will begin with me or an invited guest sharing what they are currently confused about and seeking to build a conversation with the community from there. These events will be impromptu and recorded for learning purposes, but we anticipate that only selected extracts will be shared online. We may or may not give advance notice on what the session will be about. But you can be sure that it will be confusing!

The first session will be on Thursday 19th October at 4pm UK time, and be approximately 1 hour (5pm CET, 11am EST, 8am PST). Click the button below to register.

Finally, this Monday we have Bonnitta Roy joining us for our second event in our series “What’s going on with time in a time between worlds?”

Bonnitta’s session “Weaving Time” will take place on Monday October 16th at 4pm UK time (5pm CET, 11am EST, 8am PST).

So much to appreciate in this lucid exploration of murkiness, ambiguity, and disorientation. In this moment, I'm particularly resonating with the etymology of confusion: "The literal meaning of con-fusion is something like 'with (discomforting) togetherness." Developing our collective capacity to be "con-fused" with each other might be one of the most essential socio-cultural shifts we need to navigate the metacrisis

For what it's worth...I find more trustworthiness in one who is consistently vulnerable and transparent in their confusion over one who is steadfast in purporting to know, bypassing living in the question(s) and the possible optimal discomfort that may initiate radical change or true transformation. Thanks for the leading through embodying JR ;-)