Music, Metacrisis & Metanoia

How music's spiritual power enables us to respond to the roots of civilisational crisis.

Over the coming weeks at Perspectiva, we’ll be exploring the potential and possibility of music as a response to the metacrisis, and a gateway to metanoia. Time will tell what exactly this means, but we feel the call, the essay below is a great start, and the important thing is to begin. We envisage that this project connecting music to the challenges of our times could rapidly evolve and expand through partnerships of various kinds, so please share your interest as we go.

Music is not the currency of any old power, and certainly not the power to coerce. When sounds find their feet and their form, music dances beyond the horizon of mere ideas. Music is known to the body and the mind but its jurisdiction is the soul, and its mandate stems from our experience of life as a whole. Music takes us beyond our senses to our sensibilities, beyond the empirical and the factual to the transcendent and the possible. As a primordial affordance for the act of creation, music is an indigenous, inter-generational, and universal language, a wellspring of memory for the intimation of new worlds. Music is the past flirting with the present, no doubt, but it’s also the beating heart of the future.

The project will be led for Perspectiva by our Associate Director of Community, Michael Bready (himself a musician and author of the essay below), and we’ll be hosting three live events on the subject. The first will take place on Wednesday 14th of February at 4pm UK time (5pm CET, 11am EST, 8am PST) with Michael leading an experiential workshop, exploring music’s capacity to enlighten, ensoul and enchant by engaging with music as metaphor, as spiritual practice, and as realisation.

On 28th Febrary at 4pm UK time (5pm CET, 11am EST, 8am PST), Greg Thomas will join Michael and myself for a conversation to explore the potential and possibility of music's social and cultural impact by exploring the African-American musical heritage. Greg Thomas, CEO of the Jazz Leadership Project, is a writer, teacher and entrepreneur as well as host of the Omni-American Podcast.

Finally, on 4th March at 4pm UK time (5pm CET, 11am EST, 8am PST), Brother Phap Linh of Plum Village Zen Centre will join the conversation to explore music’s potential to support spiritual practice. Before becoming a monk, Br. Phap Linh studied mathematics at Cambridge and worked as a professional Cellist and Composer. He is now a senior Dharma teacher in Thich Nhat Hanh’s Zen lineage and continues to compose music.

In related news, I’ll also be holding a Leading from Confusion session on Thursday 22nd February at 4pm UK time (5pm CET, 11am EST, 8am PST), probably on the subject of peace. To join this session, please sign up to our community here:

Jonathan Rowson, Co-Founder and CEO of Perspectiva

[The picture above is of Bootsy Collins - bass player for James Brown and Parliament/Funkadelic]

On the opening track of Parliament’s 1975 masterpiece album, Mothership Connection, George Clinton declared “The desired effect is what you get, when you improve your interplanetary funksmanship!”

By the mid-1970s Clinton and the larger musical collective which he created (Parliament/Funkadelic, or simply P-Funk) had been crafting their mythology for several years. Outrageous, hilarious, absurd, and yet still profound, it was a complex mix of science fiction, Afro-futurism, religious symbolism and sharp social commentary. With over the top stage shows, featuring the arrival of spaceships carrying messianic-shamanic figures like Dr. Funkenstein, funk was deemed a sacred primordial force with a transformative and liberatory spiritual power - a path to awakening. “Free your mind, and your ass will follow… The Kingdom of Heaven is within!” went the anthemic chorus of Funkadelic’s 1970 album “Free your Mind”.

At first glance, P-Funk mythology might seem like just an extravagant joke. However, such a view overlooks the spiritual depth of the music, as well as the important lessons it offers on how music can address the challenges of our times. As well as a theatrical spectacle uniquely its own, P-Funk was also a continuation of the African-American musical tradition of speaking to the depths of human experience and the social context of the time. The historian and author Ricky Vincent described P-Funk performances as post-modern rituals in which everyone could participate. But, to my mind, by oscillating between the silly and the serious, the ludicrous and the life-affirming, the playful and the profound, P-Funk prefigured the metamodern turn in culture.[1]

A powerful example of this oscillation is the clip below from a live concert in Houston in 1976, where Glen Goins calls down the “Mothership” - the spacecraft that acts as the symbolic vessel of funk connecting Earth to the higher realms of cosmic funkiness. The narrative is deliberately silly, but Goins’ soaring vocals harken back to the gospel tradition, expressing both deep pain and a yearning for deliverance. The result is at once exalting and confounding.

The link below starts 6 minutes in when Goins takes centre stage. If you watch for 5 minutes you’ll see the arrival of the mothership, the appearance of Dr Funkenstein, and the pendulum swing from earnest psalm to laid-back rap.

For more than a century, African-American music has been a profound and compassionate existential response to the challenges of human experience: speaking to pain, affirming life, giving hope, affording transcendence, and confronting tragedy. I am not a native of this musical tradition, but rather a long-time devotee. Thanks to my dad, all I listened to growing up in Glasgow, Scotland, were blues and soul artists like Ray Charles, Buddy Guy, Otis Redding and Aretha Franklin. While this music comes from a distant land and the historical experience of people I cannot know directly, it nonetheless feels a part of me. It’s in my bones.

It might be that I was so drawn to this music because my native spiritual culture felt so empty. I was brought up Catholic and each week we would go to mass, but I never found it spiritually animating. Jesus seemed nice (I was told he loved me) but the rest of Catholicism was like an empty husk. Whatever spiritual nourishment it may have once afforded had withered and dried out long ago. My predominant experience was boredom, and the music, sad to say, was terrible. In contrast, when listening to blues, soul and gospel the world swelled up with beauty. The music coursed through my body like a drug, filling me with joy and life with meaning.

For a long time I assumed music was a largely hedonic thing - something that felt good, but of no more significance than the pleasure it affords the listener in the moment. However, in recent years, I’ve become more curious about the spiritual power of music, and its relevance to our current predicament - the metacrisis: the multiple, interlocking crises threatening life on Earth and the continued existence of our still young planetary civilisation. (For a fuller exploration of the term metacrisis see, Prefixing the World by Jonathan Rowson).

The metacrisis is the world as we’ve known it for the last 500 or so years coming to an end, with the next world not yet born. Because of its multidimensional nature, our response will need to be multimodal. We may need new systems of food production and distribution, renewed or reimagined institutions, new forms of political and economic cooperation, perhaps a move from centralised to decentralised power. However, all of these innovations will be insufficient if they are not accompanied by a deeper transformation of consciousness.

For Rowson, the root of the metacrisis is a “multifaceted delusion” caused by a “persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality”. If the metacrisis arises from humanity’s relationship to reality being somehow askew, music’s potential lies in fostering a transformation of consciousness that can bring us back into right relationship. Let me be clear, I don’t believe music alone can address the myriad problems we face, but I increasingly believe it (along with the arts more generally) are necessary to inspiring a collective metanoia.

Metanoia, from the Greek “meta” meaning change, beyond or after, and “noia” meaning thought or mind, denotes an inner transformation akin to a spiritual awakening or conversion. In the synoptic Gospels, it is the first word Jesus speaks and is most often translated as “repent”. And while it does infer a movement away from old ways of being, it signifies more than simply feeling sorry for one’s sins. For Father Ron Rolheiser, it is a movement from fear and self-protectiveness to trust and love - a journey from paranoia to metanoia. It may require, as Jung argued, a painful dissolution of self and world as one has known it, for a truer, more beautiful life, self and world to emerge.

To my mind, transformation through metanoia is threefold. Firstly, it involves a fundamental shift in our structure of value - what we most deeply love and care about. Before a metanoia, the concerns of the ego-self predominate, but afterwards, there is a profound reorientation to spiritual aims that transcend the self. Relatedly, there is a transformation in what we know. Our understanding of reality, and of our place and purpose within it is radically altered. This transformation in loving and knowing are intimately related, just like falling in love, where coming to value the person and discovering who they are unfold in tandem. And finally, there is a transformation in what one practises. After the initial revelation comes the painstaking work of changing one’s life and behaviour to be in accordance with the new realisation.

As such, a collective metanoia requires a widespread transformation in what society values, our understanding of reality, and in what we collectively practise. This, like a spiritual conversion is not the end but the beginning - a necessary first step to addressing the metacrisis. In each of these respects, music offers hope.

Music is an ancient and deep part of our nature. It is one of the earliest modes of human communication, predating (according to many researchers) the development of language. Indeed, babies respond to the prosody of the human voice (its melodiousness and musicality), far before they understand words.[2] Just as two strings tuned to the same pitch will vibrate together when one is played, music enables different consciousnesses to resonate together: a song expressing pain and sadness brings to life the same emotions in the listener, producing a shared emotional and embodied experience. Research shows this is true across cultures.[3] For some traditions, such as Hinduism, music is not limited to the human experience but viewed as a sacred manifestation of the divine with sound permeating all levels of the cosmos. Similar sentiments can also be found in the West. Johann Sebastian Bach, for instance, believed the “final purpose of all music… is nothing other than the praise of God and the recreation of the soul.”[4]

[A painting by José Malhoa titled “Fado”, which depicts a rendition of the mournful Portuguese musical style of the same name.]

In the late-modern West music is often reduced to mere entertainment, and as such, we have lost touch with its spiritual power to enchant, ensoul and enlighten. If we are to respond to the challenges of our time, we will need to rediscover music’s capacity to nurture metanoia and develop new cultural forms that consciously embrace this purpose. To better understand music’s transformative potential, it is important to understand that we can engage with music in many different ways. I’d like to explore three different conceptions of music that reveal how it can illuminate the nature of reality (enlighten), support personal transformation (ensoul), and take us into direct contact with the sacred (enchant). These three conceptions are, respectively: music as metaphor, music as spiritual practice, and music as realisation.

Music as Metaphor

At the encouragement of his mother, Albert Einstein began to play the violin at the age of 6 and grew up to become a talented musician, continuing to play throughout his life. He once shared in an interview with George Viereck in 1929, “if I were not a physicist, I would probably be a musician. I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music. I see my life in terms of music… I get most joy in life out of my violin”.

For Einstein, music was more than just a source of pleasure, it also influenced his cognition and facilitated his scientific discoveries. Speaking with the educator Shinichi Suzuki, he once stated “The theory of relativity occurred to me by intuition, and music was the driving force behind that intuition. My discovery was the result of musical perception.”[5]

In the music of Mozart, Beethoven and Bach, Einstein encountered a world where relationships are paramount. A note by itself has no meaning, significance, or truth. It’s not right or wrong, happy or mournful, major or minor, sad or ecstatic until it comes into relationship with other notes. If the key is C, then E, G and Bb create a bluesy, warm and happy chord called a dominant 7th. Listen below:

If the key is C# however, then E, G and Bb create a diminished chord, a stack of minor thirds that can create a feeling of anxious tension and a desire for resolution.

The emotional meaning of the chords is entirely different, and all because of the smallest step change of one note in the western musical scale - one semitone. Perhaps it was the relational nature of music that offered a metaphorical doorway for Einstein, enabling him to see beyond the disconnected worldview of Newton where space and time are platonic constants to a relational cosmos where gravity, space and time inter-are.

For Lakoff and Johnson, metaphors are not just rhetorical devices but are central to our structure of thinking and understanding.[6] Grounded in the physical reality of our embodied experience, they provide a framework for understanding complex and abstract concepts by relating them to familiar experiences. This is crucial to understanding aspects of reality that are not immediately tangible or visible, and may be especially important in our time of hyperobjects like climate change, ecological breakdown and the metacrisis.

Interestingly, we describe music using metaphors - “those chords have so much warmth”, as well as use music as a metaphor to describe other aspects of reality “That film had a great tempo, a great rhythm.” To draw on Iain McGilchrist’s view that the right hemisphere “presences” reality and the left hemisphere “re-presents” it, music is at once something deeply embodied and experiential, and also a representation of human experience. This may be why it is such a powerful and rich source of metaphor.

In McGilchrist’s The Matter with Things, he regularly uses music to reveal deep truths about the nature of the cosmos.[7] To paraphrase some of his ideas which apply to both music and reality as a whole, music is all about the interplay of parts and wholes - the dance of unison and differentiation; the oscillation between consonance and dissonance, tension and resolution; it is not a “thing”, but a process; to play music well, means to get in flow, to be in the groove, and “is to feel oneself played by, as much as playing, the music” (p. 13). For many people, this is what life feels like in moments of ecstatic experience, or when we are truly flourishing - we become one with reality, flowing with the unfolding. Music, especially forms like jazz or raga as McGilchrist points out, is a balance between constraint and freedom - rules and improvisation. And finally, as has been discussed, music - like the whole cosmos - comes into being through relationships, “both those between notes and those between individual consciousnesses” (ibid). As the ancient Hindus intuited, music mirrors deep aspects of reality.

The metaphors that music offers can be profound, offering insights much needed at this time. Take harmony for instance. At first glance one might think that it emerges from notes that fit well together - what’s known as consonance. Consonant intervals are those in which the wavelengths of each note sync up regularly. The most consonant interval, for instance, is an octave where the wavelength of the higher note is double the length of the lower. The next most consonant interval is the fifth, the two sound waves having a ratio of 2:3.

Equating harmony with consonance is not the whole truth, however. If you only play notes that are very consonant, all you’ll end up with is a boring melody that sounds like a deranged nursery rhyme. There is too much order. The soulfulness and beauty of musical harmony actually arises when notes that have dissonant intervals are played together but enfolded within the context of a greater whole so that their relationship makes sense. It is the interplay of dissonance, not consonance, that creates beauty.

At this time of metacrisis, many people speak about the need for a new story, a new guiding myth, as though, if we could all just agree on some positive new vision, we could work together to get through these troubled times and arrive in the promised land. The problem with this, aside from its unlikeliness, is the danger of such a story being totalising, bringing too much order and conformity. Rather than a singular vision, it is more likely we will need to find harmony amidst dissonance, just as a symphony is a harmony of disparate and dissonant elements creating a more beautiful whole.

Music as Spiritual Practice

While music can offer insights into our world and ourselves, illuminating deep truths about the nature of reality, it does not follow that this alone will transform how we live. It is one thing to know at the level of the intellect what is wise and quite another to embody and enact it. Jonathan Haidt’s metaphor of an elephant and rider to describe the human psyche is revealing in this regard.[8]

In Haidt’s analogy the rider symbolizes the rational and conscious part of our mind, while the elephant symbolizes our emotional, instinctual and unconscious self. The elephant is large and powerful representing our older, automatic and reactive evolutionary drives. The rider, in contrast, represents the newer evolved capacities for reasoning, abstract thought, and planning. What’s key in Haidt’s metaphor, is how the two interact. The rider might appear to be in control directing the elephant through reason, but in reality, the elephant’s sheer size and strength means it ultimately decides the direction of travel. This is what the ancient Greeks called akrasia, which means “lacking command over oneself”. We can see what is the right thing to do, but due to desire or cowardice, we do the opposite. And it’s the reason spiritual practice is so necessary. It is a way to train the elephant.

Spiritual practice aims at an inner alchemical process whereby old habitual tendencies are transformed in the direction of greater self-understanding and virtue. This is often not easy. It can involve making contact with parts of ourselves we dislike, what Jung called the shadow. It requires us to confront aspects of our conditioning and upbringing, various traumas we might have experienced, and reckon with the existential condition of being a finite and mortal human being.

Of course, it can also open us up to a much greater appreciation of the beauty and goodness of life, helping us to become more loving and wise, and increasing compassion, both for ourselves and for others. It brings reward, but not without challenge. Perhaps it is this that led the Tibetan Buddhist teacher Chogyum Trungpa, to famously say:

“My advice to you is not to undertake the spiritual path. It is too difficult, too long, and too demanding. I suggest you ask for your money back, and go home. This is not a picnic. It is really going to ask everything of you. So, it is best not to begin. However, if you do begin, it is best to finish.”

In our current time, we might respond, “what if we have no choice?” If the elephant is so often in control within the individual human psyche, the collective elephant driving the metacrisis is much greater and more destructive. Our civilisational akrasia is leading us to destroy our only habitat and consequently, the need for spiritual practice has never been greater.

In religious traditions throughout the world, music has always been a primary feature of spiritual practice precisely because it speaks to the depth of our being (the elephant) encouraging it in a more positive direction. In Buddhism, for instance, there is the chanting of ancient sutras; in Christianity, choral evensong; in Islam, the melodious style of reciting the Quran known as Mujawwad; and in Hinduism, devotional songs expressing love for the divine known as Bhajans.

For many years, I have been a practitioner of meditation and have regularly visited Plum Village - Thich Nhat Hanh’s Zen Monastery in France. During morning meditation one of the monastics will have the task of singing the morning chant. This includes precise sounding of a bell and a beautiful, ethereal melody. Towards the end, they’ll sing a phrase (namo shakyamunaye buddhaya) three times which the community sings in response. When the final bell is sounded to signal the beginning of silent practice, it often feels to me that a spell has been cast. The present moment feels more alive with mystery and the meditation session is somehow charged with greater intensity and profundity. You can listen to an example below, though please bear in mind the recording does not capture the live experience:

This is an example of how music can support spiritual practice, but it can also play a far more central and pivotal role. Two modalities that have gained a great deal of attention in recent years are holotropic breathwork (as developed by Stanislav Grof) and the use of psychedelics such as psilocybin, LSD, Ayahuasca, and MDMA. There is a great deal of interest in how non-ordinary states of consciousness can support the healing of trauma, release old emotional patterns, and enable one to develop greater purpose in life. What is given less interest, however, is the importance of music to these transformational experiences.

In one psychedelic journey I experienced, I came to a significant point of transformation when “Seteng Sediba” by the Soweto Gospel Choir started playing. Upon hearing this song I began crying, my body started convulsing, and raw emotion flowed through. When the song finished, I turned to the person who was sitting with me and asked them to play it again. I listened to the same song on repeat for almost an hour. The voices and the drumming seemed to stream into my physical body, healing long-buried shame and self-doubt, bringing a message to love myself and all of life. Simultaneously, waves of resistance rose up within my psyche and I struggled against what has happening. Part of me knew the process was deeply valuable and another part of me fought fiercely against it. But the music kept coming and so the process kept unfolding. The music was the catalytic force.

Folk music from all over the world demonstrates that music’s capacity to speak to the depth of human experience is not limited to explicitly spiritual or religious contexts, but can emerge as a widely practiced cultural art form. The blues, for instance, although often described as secular, is nonetheless an existential response to the vulnerability of human experience. Greg Thomas describes the blues as a home-grown wisdom tradition, one which embodies a post-tragic sensibility - the hope, the agency, and the humanity on the other side of despair: a sensibility we may need much more of in the coming years. To play and listen to blues is to be in touch with one's vulnerability and the difficulties of life, and yet participate in a music that offers a compassionate, soulful response, affirming life in the midst of suffering. John Lee Hooker’s 1960 recording “No Shoes” is a good example:

In my view, however, there is something especially powerful about engaging with music for consciously spiritual purposes. The participation in music itself becomes an act of devotion - moving the soul in the direction of the sacred. The counterpart to blues in the African-American tradition is gospel. Where blues is secular, gospel is religious; where blues sinks into the Earth, gospel ascends to Heaven. In some ways they are opposites - but their relationship is also deep and symbiotic. Gospel music doesn’t get to heaven by ignoring the tragic aspects of life, instead it uses the raw energy of human experience in the realisation of transcendence.

Musician and writer Gregory Tate says the following of Gospel, “There’s this notion of spirit possession that comes from Africa, that’s part of seeking a certain kind of release and catharsis. This is an irruption of Spirit to arrive at an inner peace, through being completely, expressively open.”[9] This is where music as spiritual practice becomes music as realisation. Below is a short clip from the 2018 documentary “Amazing Grace”, that provides an example of just what Tate is speaking of.

Music as Realisation

While, music as metaphor can illuminate the nature of reality and music as spiritual practice can enable the inner transformation needed to live in right relationship with reality, it is perhaps music as realisation that offers the most powerful pathway for bringing about a collective metanoia, because it allows us to fall in love with reality.

Years ago I had the opportunity to sit in the meditation halls at Plum Village and listen to Thich Nhat Hanh give Dharma talks. He would always emphasise the basic practices of mindful breathing, walking and eating as the core of the path - crucial to cultivating true presence, to be fully alive, aware, and in touch with reality.

I remember being struck by the fact that he always seemed to be completely and fully present in every moment: when walking to the meditation hall, eating lunch, putting on his jacket, drinking tea, in conversation with others etc. I had been practising meditation for many years when I first went to Plum Village, and had become familiar with just how easily my mind could wander, and how frequently I could lose myself in habit energies of restlessness, craving or anger. To witness someone so present, serene, and - at the age of 83 - vital, was remarkable. I’ve learned a great deal from the Plum Village tradition, but there is perhaps one teaching that has been particularly significant to me. I’ll let Thich Nhat Hanh’s own words convey this message. This is an excerpt from the fifth of ten Love Letters to Mother Earth:

“Dear Mother Earth, There are those of us who walk the Earth searching for a promised land, not realizing that you are the wondrous place we’ve been looking for our whole lives. You already are a wonderful and beautiful Kingdom of Heaven—the most beautiful planet in the solar system; the most beautiful place in the heavens. You are the Pure Land where countless buddhas and bodhisattvas of the past manifested, realized enlightenment, and taught the Dharma. I do not need to imagine a Pure Land of the Buddha to the west or a Kingdom of God above where I will go when I die. Heaven is here on Earth. The Kingdom of God is here and now. I don’t need to die to be in the Kingdom of God. In fact, I need to be very much alive. I can touch the Kingdom of God with every step.”

The pithiest expression of this sentiment (often depicted in Zen calligraphies) is “This is it”. This is what I mean by music as realisation. Music is not only a metaphor for truth, goodness, and beauty, it doesn’t just point towards the sacred - it is the realisation of sacredness itself. To draw on the Zen tradition, it’s not just the finger pointing towards the moon, it is the moon itself. It is reality expressing itself as a joyful, beautiful manifestation. The realisation of the sacredness of Being arises when our consciousness and music enter into a profound relationship with each other.

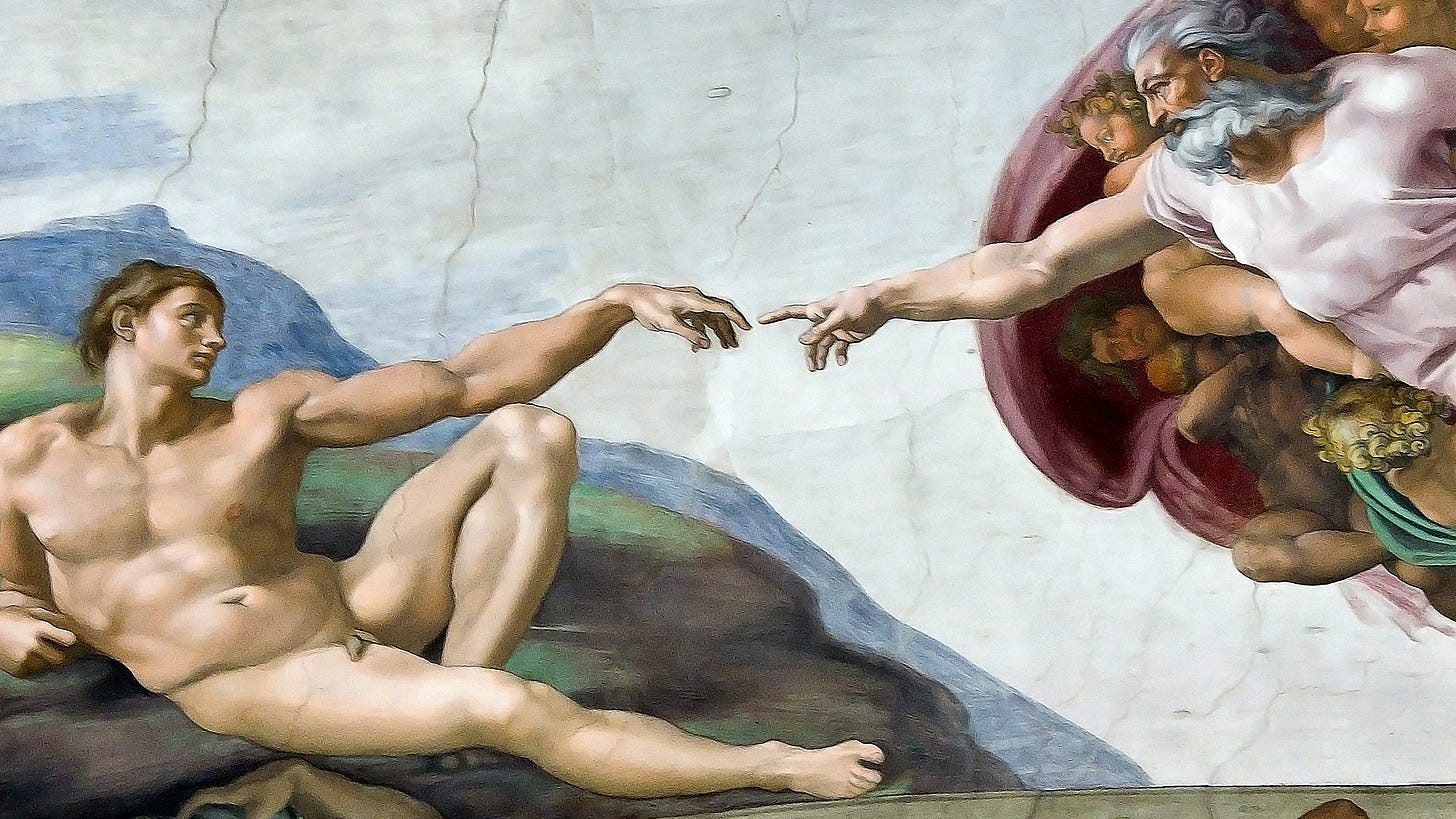

Zen teaches that the sacredness of Being is everywhere all the time, and it is just a matter of waking up to that reality. A similar sentiment is expressed in Michelangelo’s painting on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, The Creation of Adam. The painting shows God reaching out to Adam and Adam reaching back to God. If you look closely, however, it becomes evident that God’s hand and finger are fully extended but Adam needs to raise his finger to make contact, implying that God is available and reaching out to us all the time and it is our responsibility to reciprocate.

If I can be permitted to add another dimension to this, music is God calling to Adam, singing to him, urging him, to raise his finger and participate in sacredness. It may well be true that Nirvana, God, Brahman, is available everywhere all the time, but music makes the sacred more palpable, more available to us.

I was fortunate to have a visceral experience of this last year when my wife Kylen and I visited Buenos Aires. One evening we were walking through the neighbourhood of San Telmo. Looking down one street we saw a crowd of people and could faintly make out the sound of a band playing, so we ventured in that direction. We discovered a beautiful scene. People of all ages, from different parts of the world, were singing, clapping and dancing to songs freely offered by musicians deep in the flow of creating. Around this time, I was thinking a lot about the troubled state of the world, and yet here, in this little corner of Buenos Aires was a bubble of heaven. If we could only learn to do more of this, I thought, the world would be ok. Here’s a video I took at the time:

This scene is the fruit of countless conditions - a peaceful society, a rich cultural tradition, musical education, the absence of crushing poverty (at least for this small part of Argentina). What is not so easily appreciated, however, is that this collective experience has causal power. It nourishes the soul, gladdens the heart, and re-sanctifies the world, nudging it in a wiser, more beautiful direction. If we are seeking a world where there is widespread appreciation of the sacredness of life, we need to experience the sacredness of life here and now. To mix the words of peace activist A.J. Muste with Charles Eisentien, there is no way to a more beautiful world, the more beautiful world is the way.

Recently John Vervaeke, Daniel Schmactenberger and Iain McGilchrist engaged in a 3.5 hour conversation titled The Psychological Drivers of the Metacrisis. A predominant theme in the discussion was the loss of a “sense of the sacred” and a need to rediscover this collective orientation. Indeed, a brief search of the transcript shows that the term “sacred” came up 52 times, and not just in one brief section of the conversation but throughout. At one point Vervaeke said the following: “There’s two poles to this: For us to fall in love with being again - that’s the agent pole. But the world as an arena in which we can act, it has to be sacred to us. Sacred is how the world is to us when we are falling in love with it.”

“Sacred is how the world is to us when we are falling in love with it.”

This, I believe, is the most powerful transformation of consciousness that music can enable, and the most necessary for us to respond to the metacrisis: realising the sacredness and beauty of life and thereby enabling a falling in love with reality. Importantly, this is realisation both in the sense of recognising and making real. They are one and the same - the recognising is the making real. It is through this metanoia that we will value that which is truly valuable, and develop the care and courage to act in service of a more beautiful future. If someone can have a direct experience of beauty through music, that can then unfold into an appreciation of the beauty and sacredness of reality as a whole. Importantly, this is not just sacredness and beauty as an idea, it is participation. Through music we can collectively resonate in the beauty, joy and sacredness of Being.

The Outro

The renegade psychedelics pioneer Timothy Leary was the first to talk about the importance of “set” and “setting”. “Set” refers to the mindstate that you bring to a psychedelic journey - your intention, your readiness, your openness. “Setting” refers to the context in which you engage with psychedelics - who’s around you, your environment, the sounds and sights etc. A bad set and setting and you’re likely to have a bad trip. A good set and setting and the experience is more likely to be valuable.

Today, we are not harnessing the full spiritual power of music because our economic system and spiritually-hollowed-out culture reduces music to mere entertainment, something we consume, and in so doing we have degraded the set and setting. Last summer I had the opportunity to see the Soweto Gospel choir (who I mentioned earlier) live at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. The performance and music was of the highest quality, but I left feeling disappointed. The experience didn’t enchant. It was pleasant and impressive, but not transcendent or transformative. And I put this down to the set and setting. The audience shuffled into the auditorium, sat passively in their seats, watched the performance and then left. Although the music was full of spiritual sentiments, there wasn’t any conscious spiritual purpose - we were there to be entertained; and there was no broader spiritual context - no accompanying practices, myths, calls to wonderment.

We need to learn how to enfold music within a larger spiritual context and purpose, i.e. generate the right “setting”. And we need to develop the conscious intention to come together with others to resonate in an experience of beauty and sacredness, i.e. generate the right “set”. What’s more, we need to learn to do this in a time when increasing numbers of people find the religions of old unappealing - especially their dogmatic metaphysical and cosmological claims. This will require the creative development of new cultural forms and communal activity.

The metamodern sensibility emerging in the culture at large provides fertile soil for this to change. There is a readiness for music that speaks to the challenges of our times and affirms the sacredness of life. By transcending the need for metaphysical certainty characteristic of modernity and the religions of old, as well as the metaphysical skepticism of postmodernity, metamodernism facilitates a more open, exploratory and creative relationship to reality. As McGilchrist argues in The Matter with Things, if we choose so, we can be active participants in the creative unfolding of a divine reality. And as George Clinton and Parliament/Funkadelic showed, we can have tons of fun doing it. Music offers us a way. But it is up to us to take up the task.

[George Clinton on stage with Parliament/Funkadelic sometime in the late 1970s]

Footnotes

Vermeulen, T., & van den Akker, R. (2010). Notes on metamodernism. Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/jac.v2i0.5677

For a discussion on the phylogeny and ontogeny of music see McGilchrist, I. (2009). The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press. (pp. 102-105)

Putkinen, V., Zhou, X., Gan, X., Yang, L., Becker, B., Sams, M., & Nummenmaa, L. (2024). Bodily maps of musical sensations across cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 121(5). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2308859121

Butt, J. (Ed.). (1997). The Cambridge Companion to Bach. Cambridge University Press. (p. 53).

Suzuki, S. (1969). Nurtured by love: A new approach to education. (W. Suzuki, Trans.). Exposition Press. (p. 90).

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). The metaphors we live by. University of Chicago Press.

McGilchrist, I. (2021). The Matter with Things: Our Brains, Our Delusions, and the Unmaking of the World. Perspectiva Press.

Haidt, J. (2006). The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Modern Truth in Ancient Wisdom. Basic Books.

Thompson, A. "Questlove" (Director). (2021). Summer of Soul (...Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised) [Film]. Onyx Collective; Concordia Studio; Play/Action Pictures; LarryBilly Productions; Mass Distraction Media; RadicalMedia; Vulcan Productions; Distributed by Searchlight Pictures and Hulu

During the Delta wave of covid, when images of pyres burning day and night on the banks of the Ganges pulsed through the media, TikTok (a suspect platform, but that's another topic) broke out in sea shanties, those songs of communal motion and effort (leaving out the problematic whale hunting), as if the terrible fear and grief roiling in the collective unconscious was answered in the motion towards communal music. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RQ2HbYnlc3s

I have, in an armchair, lay, uncredentialed way been studying music as a potential salvific force since I read in The Master and His Emissary this: "One possibility is that music, which brought us together before language existed, might even now prove effective in regenerating commonality, avoiding the need for words, that have been devalued, or for which we have become too cynical. Let's not forget that it was with music that Orpheus once moved stones." (page 458) I have mostly focused on music in evolutionary biology and bicultural evolution, disagreeing with Dr. MacGilchrist about us not being "conniving apes." I instead think we are DIVINE conniving apes, and that much of what is called sin or evil, is vestigial and evolutionary, *but* so is music if we can reclaim it. Ellen Dissanyake, in Art and Intimacy, proposes, since music creates oxytocin (the motherhood hormone), that after the hominins left the trees for the savannah, and became bipedal, that birth needed to occur earlier, so infants couldn't cling, and the mother hominin would sing or hum or grunt to the infant she'd hidden away for a bit while gathering. In that dyad, she thinks, begins relationship, ritual, and communality.

Thus, I find this essay, and this project, ****genius****. We live in a vivisecting neo-Puritan age, so it may be that the pleasure itself (in part oxytocin) makes us discount music. The late poet Galway Kinnell said all Americans read poetry nasally as we unconsciously remember our Puritan heritage, and music is perceived by scientific orthodoxy as a byproduct (not an adaptation) of evolution, "cheesecake," but if one doesn't think it is perhaps one of the deepest, oldest, most powerful aspects of being, resonating with potential, watch this from the documentary Alive Inside https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5FWn4JB2YLU

My deepest longing these days is to be in an amphitheater or a beautiful auditorium, with a huge audience, listening to a requiem, a recognition of all that has been lost, that is still being lost, during which I know I would bend double with weeping and fall to the floor. And that perhaps to be followed by a second line, from the tradition of the Jazz Funeral in the American South.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQoreoDSqEE

So my intuition is that this is utterly brilliant, and deserves wide,wide attention, and Bring Em All In

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MxPl9Ka4yD4

Beautiful, full, and fulfilling piece/writing/insights, especially with clips of music. Thank you so very much.