Towards a Parallel Climate Regime

The case for a transdisciplinary process to drive alongside COPs and their CARs.

“What can one say? What can this dear world do, caught up in the emergent properties of its own predicament?”

- Alastair McIntosh, Riders on the Storm: The Climate Crisis and the Survival of Being (2020)

One of the hardest things to grasp about climate change is a little paradoxical, namely that it is a singular phenomenon that calls for a uniquely multi-faceted response.

Climate collapse, as it might more accurately be described, is implicated in too many spheres of life to be merely an environmental issue. It is not like the hole in the ozone layer that was relatively easy to fix, because it is not happening in one place, nor arising from one cause. Climate collapse is not a war, because most of us are on too many sides at once, though it may well call for a martial spirit. Climate collapse is not like an asteroid hurtling towards Earth, when questions of root causes and vested interests would not arise, but it is a slow-burning and then quickening existential threat to humanity. Nor is climate collapse a mere problem, because it is not clearly defined, localised, discrete and time-limited; rather it is vexed, global, porous and inter-generational. Climate change is also a predicament that goes beyond the problem-solution mentality we are all enculturated into.

With everything else that is happening, it is easy to forget about climate collapse and our apparent inability to do anything about it. Many don’t think about climate at all, and among those who do, many outsource responsibility for it to ‘the climate regime’. I came to this expression quite late, when I was a Trustee at the communications charity, Climate Outreach, but it is widely used by those who see the climate issue as a governmental and technocratic challenge. The ‘regime’ is essentially the UN process of nation states setting themselves targets and then, in theory at least, holding each other to account and it has two main modalities as far as I can tell - authoritative reports and multi-state meetings. This regime does not appear to be working, and insofar as humanity needs ‘a climate regime’ at all, it needs a much better one.

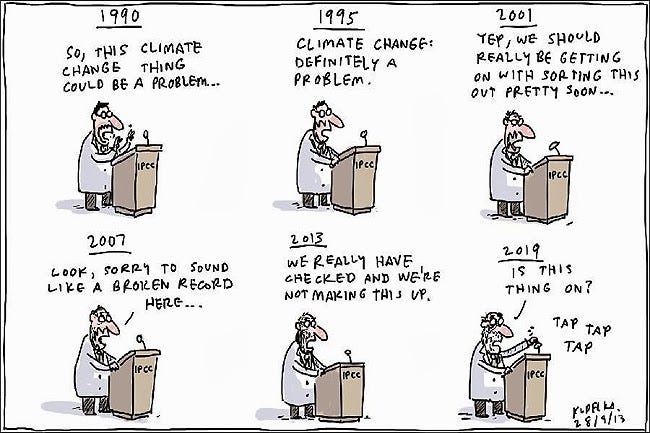

One way to understand the point of Perspectiva and the wider field we are part of is that we need different ways of knowing and new cultural and organisational forms to help us respond to collective immunities to change. This point is not climate-specific, and refers to the more general challenge of contending with modernity becoming dysfunctional and unintelligible, but it is illustrated well in the funny-but-not-so-funny global predicament highlighted by the following:1

This Kudelka cartoon called None so Deaf appeared in The Australian on September 28 in 2013. It reflects the outcome of the fifth UN climate assessment report while anticipating that 2019 would be no different. There was a kind of breakthrough in Paris in 2015, but overall, the same pattern applies in 2025. Clive Hamilton put the problem well in his 2010 essay, Why we resist the truth about climate change:

Innocently pursuing their research, climate scientists were unwittingly destabilising the political and social order. They could not know that the new facts they were uncovering would threaten the existence of powerful industrialists, compel governments to choose between adhering to science or remaining in power, corrode comfortable expectations about the future, expose hidden resentments of technical and cultural elites and, internationally, shatter the post-colonial growth consensus between North and South. Their research has brought us to one of those rare historical fracture points where knowledge diverges from power.

What can we do when knowledge diverges from power? There is no easy answer, and this is the terrain of giants like Michel Foucault, Bruno Latour and the field of Science and Technology Studies. One way to think about it, though, is that knowledge and power are reciprocally related such that within the constraints of truth and staying alive, changing one will change the other and vice versa. Perhaps there are ways to create and present knowledge that changes our idea of power and how it mobilises; and perhaps the kinds of power we need today are inextricably linked to a more reflexive relationship to knowledge, allowing it to change us, as we change it too.

One of my first Substack posts on The Joyous Struggle was called Dancing with a Permanent Emergency: Why I decided to shift focus from the climate crisis to the meta crisis. That post describes roughly a decade of working on climate change from a policy research and public communication perspective, and describes why I realised that our only hope of contending with the climate crisis was a kind of expansion of perspective and integrative capacity that is not possible within academic disciplines or sector-specific organisations. In other words, just as the economy is too important to be left to economists, and politics is too important to be left to politicians, the climate crisis is too big a conundrum to be left to climate professionals. The need for a broader constituency of actors is partly because climate collapse is not merely an issue, but more like a symptom of a much deeper and wider phenomenon called the metacrisis, which I currently define as follows:

The metacrisis is the historically specific threat to truth, beauty, and goodness caused by our persistent misunderstanding, misvaluing, and misappropriating of reality. The metacrisis is the crisis within and between all the world’s major crises, a root cause that is at once singular and plural, a multi-faceted delusion arising from the spiritual and material exhaustion of modernity that permeates the world’s interrelated challenges and manifests institutionally and culturally to the detriment of life on earth.

At some point, I ceased to be surprised by the paradigmatic inertia about climate collapse indicated in the cartoon, realised that it was part of a bigger pickle, and started trying to work on it.

The following extract captures the feeling:

Like the famous Sherlock Holmes case of the dog that didn’t bark, the most important message of most climate assessment reports is the one that is not there. The message that jumps out above all others is that previous IPCC reports, going back to 1990, have not been heeded. Where is the report on that? Because that’s the one we really need. Where is the report with IPCC-level rigour and authority that explains the gap between what we know and what we do at scale? Where is the widely reported executive summary that highlights the glaring absence of the pre-political We invoked by scientists? Where is the public awareness campaign on the competing commitments arising from democratic mandates? Where is the world stage where we grapple with endemic corruption that breaches trust, cultural conditioning that binds us to our consumer trance, and targeted technological addiction that keeps us diverted? Where are the daytime television conversations about how fascinating and tragic it is that we get in our way, and what it might take to get out of it?2

While I have had this idea for several years now, and initially envisaged a parallel report here, the answer may not be ‘a report’ as such, though for all their limitations, reports still retain some formal dignity. The output might be a book, a dance, a ritual, a wake, an ‘unconference’, or something entirely sui generis. I think it might be a report, though, because the challenge is to conceive of a cultural and institutional form with the intellectual rigour required to shift opinion, and one that allows reckoning along the lines of the existing climate regime, with a transdisciplinary ethos and similar levels of cultural, political and institutional investment.

If we are going to try to create something new, it makes sense to better understand what we already have in place.

**

The Problem with COPs and their CARs

It might sound like a joke to say that the future of the world depends on ‘the cops’ and their ‘cars’, but it’s a serious joke, and the question is what to do after you get it.

Grasping the intellectual and moral complexity of the challenge is exacting enough, but the geopolitical challenge is even more formidable. Theatre captures it best, as I experienced when I watched the critically acclaimed West End show Kyoto a few weeks ago. The play details the hard-earned creation of the UN climate change ‘regime’ and why it is so difficult to achieve international cooperation across almost 200 nation states. The play is tense, funny, riveting and highly recommended, but it was a curious experience to watch in 2025, because the form of success achieved at the end of the play felt like a portent of failure.

Yet the positive point to take away is that such global cooperation is possible, and even beautiful when it happens, as we know from the Paris agreement in 2015. While it is tempting to give up on the process entirely, it is worth trying to augment what we have, while shining a light on what exactly is not working and why.

There have been twenty-nine Conferences of the Parties at the UN, or ‘COPs’, with the thirtieth scheduled for Belem, Brazil, in November 2025. After disappointing outcomes at recent COPs in fossil fuel hot spots Dubai(2023) and Baku(2024), there are high hopes for COP30, which takes place deep in the heart of the Amazon rainforest, the lungs of the earth. Yet it remains unclear whether the evocative venue will be a difference that makes a difference, nor why we might trust governments to follow through on any agreement.

There are many ways to contend with the climate crisis at a variety of scales, and they are all connected, as detailed in The Seven Dimensions of Climate Change project that I led a decade ago. However, it is foolish to ignore the UN ‘climate regime’ because although it is about governance, it influences and is influenced by all dimensions (Science, Technology, Economy, Law, Democracy, Culture, Behaviour) directly or indirectly.

In light of the importance of the intergovernmental process, one question to ask is this: If the COPs are the ‘hardware’ of the world’s climate regime, what ‘software’ does it run on?

The main answer is the UN Climate Assessment Reports (CARs). There have been six United Nations International Panel on Climate Change Assessment Reports, beginning in 1990, followed by 1995, 2001 and 2007, each comprising an overall synthesis report informed by prior contributing assessments. The latest CAR synthesis report for 2023 can be found here, and the next CAR synthesis report is scheduled for 2029.

The purpose of these assessment reports is to

Establish scientific consensus.

Inform policy making.

Raise public awareness.

Track progress against targets,

Support global agreements.

Encourage commensurate action.

I am keen to emphasise that these reports are extraordinary scientific and cultural artefacts showing human beings collaborating with diligence to objectively describe a major planetary problem and detail the necessary features of any solution. In and of themselves, they are brilliant and necessary outputs, and they are not the problem as such. The problem is the naivety of our assumptions about the impact of information on habitual human behaviour in general and in the way power adapts to information to protect and perpetuate itself. We have failed to heed the evidence that information by itself often has little catalytic or transformative effect at the requisite speed and scale. So, yes, we need trustworthy and authoritative information more than ever, but that is merely a necessary condition of requisite climate action and not even close to being sufficient.

Beyond ‘Action!’: The Urgent Need for a Different Public Conversation

I am the tragic mask. I am how you defend yourself from what it is a catastrophe to have to know. – Ruth Padel, RSA Climate Poetry night (2015)

It could be argued that the CARs are speaking truth to power and that they are ‘working’ in the sense that things would be much worse without them. Even if that’s true, the risk is that by presuming we have a viable process, we risk losing further precious time we don’t have to avoid potentially devastating tipping points in the complex climatic system.3

At a global systems level, the preeminent question is whether fossil fuel emissions have declined in response to our understanding that they are driving climate breakdown, and they haven’t. Since the first CAR in 1990, global emissions from fossil fuels have steadily risen.

We also know, for instance, from a 2018 report from the Institute for European Environmental Policy, that “slightly over half of all cumulative global CO₂ emissions have taken place since 1990.” In other words, the shocking fact is that far from marking the moment we started to get on top of the problem, the creation and continuation of the climate regime coincided with the situation becoming significantly worse.

With the greatest of respect to the report researchers and writers, there is a strong case that these CARs are not working. The CARs are not quite ‘pearls before swine’ but that pugnacious statement is not completely misplaced because they are premised on a view of knowledge influencing action that is simply not valid. This whole climate regime is also taking up human capacity that could be effectively redirected, or at least that needs to be supplemented. Either we need a different kind of approach, or we need to supplement the existing approach with forms of knowledge that matter just as much as the CARs, but that tend to be downplayed, neglected or ignored.

I appreciate that it could also be argued that CARs are the wrong target, since they are merely a small part of a much bigger problem of a global order based on nation states, the rule of law, an unimaginative media, and the policy imperative of economic growth. That might also be right, but what follows for good work today? Aren’t these brilliant but ineffectual reports somehow symptomatic of what we need to unlearn and reimagine?

Perspectiva would like to begin a project that sheds light on why exactly these reports do not appear to be shifting cultural, political and economic conversations as swiftly as they need to, because it is past time to be more candid about the relationship between knowledge, action and inaction.

The aim is to show what it means to get beyond familiar laments about the failure to act, towards a richer conversation about the kinds of awareness, attention and astute action required to shift inertia and sclerosis. I believe that conversation is the one that needs to become much more salient for decision makers of all kinds, including mere consumers and citizens who always have more power than they realise.

Immunity to Change

There are many ways to quantify and qualify our collective immunity to change, but in his forthcoming book, A Climate of Truth, Mike Berners-Lee puts it like this:

If what you are doing is consistently not working, it is time to do something different…Everyone has a different understanding of how the world works and what will be effective…(But) nobody can really claim their approach is working since (*at the scale that matters*) nothing has worked…We need to honour these heroic failures, and somehow stand on their shoulders. To do this, we have to also peer under the surface of our failure to understand it. First, of course, we do have to understand the most obvious and superficial reasons for failure. But then we need to dig still further to see the reasons behind the reasons behind the reasons. We have to get to the core of the problem. On then will we be able to treat the causes of our failure, rather than the symptoms.

The project I am keen for us to begin would be a response to ‘heroic failure’.

It is precisely because these assessment reports are both so well-respected and yet so ineffectual that we need to attend to them. A great deal might be revealed by reporting on what they don’t report on, and thereby help to shift priorities in climate philanthropy, climate finance, climate media, climate policymaking circles, and culture at large.

The aim would be to create a parallel climate reporting process that creates a new kind of conversation about why humanity is so stuck with the timeline of COP30 (November 2025) and CAR7 (late 2029) in mind, ideally beginning the conversation with a pilot report in time for COP30 in Brazil.

The Parallel Reporting Process we urgently need: What’s missing?

The spirit of the challenge this project seeks to contend with is outlined in my reaction to the ‘Physical Science Basis’ report in 2021 shared at the start, but it would work in response to any or all of them.

The main thing that is missing is any reporting on what we are doing about our collective immunity to change. Immunity to change is a multi-dimensional idea from many schools of thought, but it is best known today through the theoretical and practical work of Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (I know Bob Kegan, and took his class when I was at HGSE in 2002-3). The immunity to change process is by no means the only theoretical tool that informs this project, but I share it here to give an idea of the nature of the work required to highlight and act upon the phenomenon Kegan has called “putting your foot on the gas and the brake at the same time” – which applies to the climate crisis.

Contending with immunity to change is one of Perspectiva’s ten premises: “We need to get out of our own way”. But this project also speaks from and to all the other premises and I think it’s best to understand immunity to change through our third premise relating to the threeness of the world (‘systems, souls, and society’) that I have been writing about over on my account, The Joyous Struggle.

There are many examples available online of an inquiry process that maps commitments alongside actions/inactions, competing commitments and hidden assumptions. We can imagine a similar process applied to any person, group or process contending with climate collapse, which is sketched for illustrative purposes below. To my knowledge, this approach has never been applied to climate change, but imagine, for instance, if a representative from a relatively affluent country like the UK undertook the process. It would look something like this:

This table is purely illustrative, but it speaks to the relationship between our ostensive commitments, what then actually happens, and how we experience it and rationalise it. The point is this:

This attempt to connect commitments with competing commitments and hidden assumptions is the kind of conversation that needs to take place at a much bigger scale.

Coming back to the stipulated aims of the climate assessment reports, I have added some first thoughts of what I feel the parallel reports might add:

Establish scientific consensus?

Yes, and research the impact of scientific consensus on political action. Consider dangers inherent in the idea of consensus & whether downplaying them may be part of the challenge. Question whether/how public opinion shapes the behaviour of elites. Create a deliberative inquiry into the relationship between science, public opinion, education, media and technology.

Inform policy making?

Yes, and question the meaning/relevance of policymaking. Advocate strategies to build social and cultural power to shape decision-making contexts. Beyond platitudes, how might cultural norms shift in ways that also 'inform policy-making'?

Raise public awareness?

Yes, and offer case studies of whether and when raising awareness matters, and what the relationship between awareness and agency is - consider how we might talk of such things, and learn and teach more about them. What is the role of social and spiritual practice in moving from awareness to agency and action?

Track progress against targets?

Yes, and question the role of targets in general, and in the context of the need for intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in particular. Create other aims and incentives that speak to the will and capacity to achieve the targets. What is the relationship between values and targets? Recognise competing commitments that may militate against achieving targets and consider how they might be addressed.

Support global agreements?

Yes, and augment global agreements in ways that recognise not only diverging responsibilities and capacities, but also cultural and political contexts, including corruption and the weakness of international law.

Encourage commensurate action?

Yes, and specify forms of action at multiple levels, not just governmental. Clarify the relationship between action at the micro-meso-macro levels and create cosmolocal conversations to reflect how that layered understanding helps with mitigation and adaptation.

**

I think the nature of work involved is transdisciplinary in the sense that it not merely goes beyond a single discipline, but also beyond a plurality of disciplines (multidisciplinary) or the interaction of disciplines (interdisciplinary). The work requires broad and deep understanding of multiple domains but also epistemological agility and ingenuity, practical nous, political maturity, and a capacity to collaborate to create new frameworks, measurements, evaluative criteria and so on. The form of expertise required to contribute to such a process is therefore distinctively transdisciplinary - it goes beyond the modality of disciplinary knowing to a post-university form of inquiry, where academic knowledge is still of great value and heeded where relevant, but it is no longer sovereign; what matters more is the pragmatic imperative to align power with knowledge (not vice versa!) and agency with a broader conception of truth. Without implying any false equivalence or even agreement, I have in mind something like what Michael Commons might call metassytemic or even paradigmatic knowing, what Ken Wilber might call ‘second tier’, what Karen O’Brien might call fractal approaches, what Donna Haraway might call sympoesis or ‘making-with’, what Nora Bateson might call transcontextual awareness, what Ben Okri calls ‘existential creativity’, and an approach that is mindful of all twelve leverage points to change a system, outlined by Donnella Meadows. I also envisage the inquiry and its outputs would be informed by the threeness of the world, or ‘systems, souls, and society’.

I have in mind the creation of an international board of people with these demonstrated capacities who would inform any resulting report and speak on its behalf. I imagine public events that would co-arise with the formal CAR and COP processes and both support them and call them into question. I see this parallel process as a kind of critical friend of something impressive that is not working.

We urgently need to give institutional and cultural attention to these matters. It’s not easy, but we believe it might be possible with a new kind of public inquiry that invites a range of interested parties to help better account for the gap between what we know and what we are doing at a planetary scale. The point is to clarify more precisely why knowledge and power have been diverging, and will continue to diverge until we have a different kind of public conversation.

Perspectiva has been thinking for a while about how best to bring this project idea to life, and we have a range of ideas that we would like to explore with interested parties. If you are in a position to begin to support this project financially, please get in touch.

Yours Aye,

Jonathan.

It has been said that we now live in a world of ‘define or be defined’, but I have always preferred to just get on with things and trust that others will figure out who you are. Of course, I might be wrong. Perspectiva describes itself in many ways. For those with a decent attention span, we are a collective of aspiring expert generalists working on the relationship between systems, souls, and society in theory and practice. When an academic asks, I tend to say we are a research and practice institute. When my hairdresser asked me recently, I said I worked in publishing. When someone from the non-profit world asks me, I say we serve as an incubator and steward of new practices and initiatives like Emerge, The Antidebate or The Realisation Festival. When someone working in education asks me, I typically say we are an applied philosophy of education and have lots of courses coming out soon. When someone religious asks me, I tend to emphasise our contribution to spirituality in the public realm. But Perspectiva’s work can also be understood as climate activism in disguise, and that’s what I want to talk about here. We call ourselves an urgent one-hundred-year project as a serious joke to reflect that ecological peril has been an enduring emergency for decades, and it will continue to be for the foreseeable future.

This statement was initially part of a foreword to a Perspectiva essay by Rupert Read on The Case for a Moderate Flank but also features in my essay: Dancing with a Permanent Emergency, where I describe why I personally shifted emphasis from the climate crisis to the broader metacrisis.

I’m thinking, for instance, of the climate tipping potential of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation or ‘AMOC’ problem, detailed in this paper in Science.

It seems to me that the collective commitments are part of the problem. Phrases like net zero and a just transition, or protecting environments, have no real meaning. Net zero is meaningless because nature doesn’t do accounting…so the solutions we present aren’t in fact solutions.

Also just because there is a scientific consensus, this merely shows us that Houston we have a problem; that consensus can’t provide a solution…enter the murky world of geo engineering. All of these are by extension a western reductionist mind that is madly out of synch with a living ( or perhaps gasping) intelligent universe that would very much like us to just stop everything we are doing and get with the (new) program. But that takes humility and letting go…of a lot of things.

there is something rather mechanistic underpinning this vitally important process. its reflected where you speak to the "soft processes" involved in the CoP "hardware". the CoP process brings planetary homeostasis into the conversation, as it were, through the amazing and diligent work of scientists of many disciplines. Homeostasis - the self-regulating interbeing of the planetary whole tends to be viewed through a lens of interacting systems. Lifeforms break down rock into soil, changing the landscape, affecting the atmosphere, altering the dynamics of the dynamics of ice and water, which affect the lifeforms and so on. Biosphere, lithosphere, atmosphere, cryosphere and hydrosphere interact and, over the recent holocene period, have achieved a certain cyclical rhythm very suitable to many mammals and primates. like us.

recently, insights have been converging from many different siloes that suggest that theres some vital (no pun intended) elements missing in this very objective and scientifically sound assessment. the notion that evolution progresses through interacting, felt, experience that is considered and responded to in a sentient manner implies that there an important organising principle is being overlooked.

the main driver of the polycrisis is not so much the neoliberal juggernaut racing us to the lip of any cliff one cares to mention, nor the collapse of democracy, or whatever else, but rather the unquestioned assumptions in regard the nature of human being-ness that underpins the dominant paradigm and its essential institutions. our indigenous neighbours and ancestors held an understanding of inter-being with planetary processes that called upon them to consider their decision-making within that superordinate frame. tis sensibility informs many of the world's major spiritual tradition - most dramatically indicated, perhaps, in the story of Buddha's first act on achieving enlightenment being to touch the earth as witness. when biology, social science, neuropsychiatry, quantum physics, ecologists, and eco psychology begin to see the indivisibility of our selves from the systems of which we are part - including our thin slice of Psyche within a greater interacting sentient intelligence - it is time to recognise the role of Psychosphere in the homeostatic process.

Psychology is beginning to recognise the impact of the feedback on our individual psychological well-being - eco-anxiety, climate grief, and so on are becoming familiar terms. In a pathological based, cause/effect world-view, we tend to default to seeing these asa some sort of harm being done to us personally and collectively. This is like seeing the pull of gravity as a personal comment on one's approach to cycling. The rise in mental disorders and their naming reflects the desire to end a source for our discomfort and unease that can be treated without questioning the underlying drivers. this is where psychology remains captured by degenerative cycles and worldviews. Homeostasis, a regenerative process developed over 14bn years, is pushing back, inviting us to review our relationship with balance. this is not merely a political or even economic call. It speaks to our understanding of who we are and where we fit, because until that question is addressed by accepted science - including psychology - the many opportunities to address how we approach identity and belonging will remain off the table.